Ancient Rabbinical References to Jesus

Ancient secular history supports Jesus being a real person.

Quick Facts:

- Ancient rabbinical literature confirms the historicity of Christ

- This literature is supplemented by other secular sources

- There is no reason to doubt the existence of Christ in ancient Israel.

Ancient rabbinical references to Jesus confirm the historicity of Christ in addition to secular sources. Another blog referenced some secular references to Christ, while this blog evaluates extra-Biblical rabbinical references.

Rabbis often comment critically on Scripture passages in the Old and New Testaments. These comments provide a historical evaluation of Jewish thought on various issues for the past several millennia. This is not a particularly easy field to study,

To search in Rabbinic literature for data on any historical subject is a daunting task. The sheer bulk of the literature, its baffling complexity, and (to us) lack of logical structure, in complicated oral and literary history, and the consequent uncertainty about the date of the traditions it preserves, all make it an uninviting area for most non-Jewish readers. Add to this the fact that history as such is not its concern, so that tidbits of “historical” information occur only as illustrations of abstract legal and theological arguments, often without enough detail to make it clear what historical situation is in view, and the task seems hopeless. In the case of evidence for Jesus we have to the further complicating factor that he was for the Rabbis, a heretical teacher and sorcerer, whose name could scarcely be used without defilement, with the result that many scholars believe that they referred to him by pseudonyms (e.g., Ben Stada, or Balaam), or by vague expressions like “so-and-so.”

Rabbinical References to Jesus

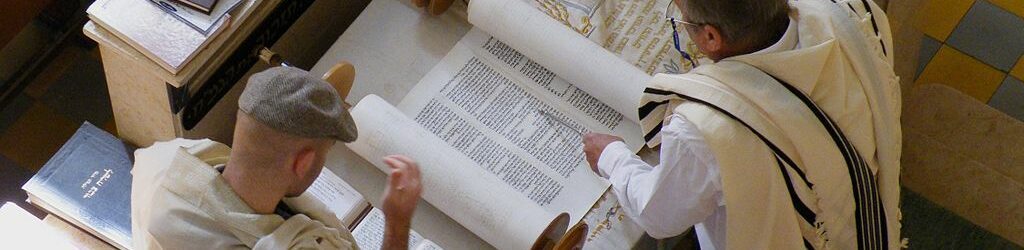

Various divisions of rabbinical literature are largely unfamiliar to the modern Christian. Various groups of scribes and rabbis began to opine on the meaning of various scripture from the time of Ezra and the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem. Generation after generation of subsequent scribes and rabbis would add to this ever-growing body of literature in an unbroken tradition.

By Christ’s day, the number of detailed writings by various scholarly individuals was overwhelming. Furthermore, little if any of this fast sum of knowledge was actually written down, but rather communicated from memory. This is the “tradition of the elders” referred to by the New Testament.

These interpretations were considered as authoritative as the written Scriptures, even though they were not thought of as directly sponsored by God. This would cause Christ to say, “You nicely set aside the commandment of God to keep your tradition.”

It was a herculean task for the Rabbinical student to memorize this vast amount of information. These students spend so much time trying to memorize and interpret these Rabbinical sayings – not to mention read the Scriptures themselves – that Christ would say,

You weigh men down with burdens hard to bear, while you yourselves will not even touch the burdens with one of your fingers.

In the Old Testament, Ezra had to specifically warn of this tendency to

set his heart to study the law of the Lord, and to practice it, and to teach His statues and ordinances in Israel.

Oral Rabbinical Tradition Transformed Into Writing

The fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD caused the Pharisees to worry that the oral tradition might be lost or corrupted. They decided these traditions must be written down to preserve them for posterity. With Rome’s permission, they moved their headquarters out of the destroyed Jerusalem to Jamnia close to the Mediterranean coast. They reformed the Sanhedrin with Yohanan ben Zakkai as the new president. He was one of the most important Jewish figures of his time, and his name is often preceded by the honored title “Rabban.”

This group saw to put their oral tradition into writing and arrange the writings by subject matter. This work was interrupted by another Jewish rebellion from ben-Kokhba, which was crushed by the Romans in 135 AD. By about 200 AD, Rabbi Judah the Patriarch finished the compilation of oral tradition into written form as the Mishnah.

Mishnah literally means “teaching” or “repetition.” The material is divided into six Sedarim, with each Seder covering the teaching of a particular subject. The six main divisions of the Mishnah are agriculture, feasts, women, damages, hallowed things, and cleanliness. Each of these subjects is further divided into smaller sections called tractates, with each tractate further divided into chapters containing “sections.”

Parallel to the development of the Mishnah was the Midrash. Its meaning derives from the verb darash meaning “to seek, explore or interpret.” The Midrash is more of a Scriptural commentary, while the Mishnah represents Rabbinical interpretations independent of their scriptural basis. There are two kinds of Midrash: Halakhah, which is more legislative and legal, and Haggadah, which is more inspirational.

The Tosefta is another body of commentary from the Tannaitic period that was not selected for the Mishnah. This means “addition” or “supplement.” These might be analogous to appendices at the end of a book. The Tannaitic period is between 70 to 200 AD referring to the Tanna’im or “repeaters” of the material in the Mishnah and Tosefta. During this period, more traditions were produced external to the Mishna, and these were known as the Baraithoth and preserved in the Gemara (commentary on the Mishna) of the Amoraic period.

The Amoraic period extends from the third through the sixth centuries AD. During this period, two schools of Amoraim developed; one in Palestine, which compiles its Mishnah and Gemara), and one in Babylon, which also produced its own commentary on the Mishnah. The Mishnah and Gemara were brought together in each group into the Babylonian Talmud and the Palestinian Talmud. The literal meaning of “Talmud” is “learning.”

Very early writings from this period show rabbinical references to Jesus that unwittingly establish him as a historical figure who practiced “sorcery” and was executed for what he taught.

Rabbinical References to Jesus

Rabbinical Literature

In this vast body of literature, both Christian and Jewish scholars believe there are several unambiguous rabbinical references to Jesus. This is remarkable as the Jewish communities deliberately censored themselves, not to mention Jesus, to avoid further persecution. In this regard, Morris Goldstein, former Professor of Old, and New Testament Literature at the Pacific School of Religion notes,

Thus, in 1631, the Jewish Assembly of Elders in Poland declared: “We enjoin you under the threat of the great ban to publish in no new edition of the Mishnah or the Gemara anything that refers to Jesus of Nazaraeth. … If you will not diligently heed this letter, but run counter thereto and continue to publish our book in the same manner as heretofore, you might bring over us and yourselves still greater sufferings than in our previous times.

At first, deleted portions of words in printed Talmuds were indicated by small circles or blank spaces but, in time, these too were forbidden by the censors.

As a result of the twofold censorship, the usual volumes of Rabbinic literature contain only a distorted remnant of supposed allusions to Jesus.

Rabbis during the “Second Temple Period” seldom referred to events or people of their period unless they were highly relevant to the Scripture being considered. The Jewish scholar Joseph Klausner wrote,

The Talmud authorities, on the whole, refer rarely to the events of the period of the Second Temple, and do so only when the events are relevant to some halakhic discussion, or else they mention them quite casually in the course of some legends. What, for example, should we have known of the great Maccabaean struggle against the kinds of Syria if the apocryphal books 1 and 11 Maccabees, and the Greek writings of Josephus had not survived and we had been compelled to derive all our information about this great event in the history of Israel from the Talmud alone? We should not have known even the very name of Judas Maccabaeus!

Christ lived during the Second Temple Period, so references to him in ancient Jewish literature and tradition are even more noteworthy. Many of the ancient rabbis living during the Roman occupation were much more concerned about their oppression by a Gentile nation than an itinerant preached named Jesus; Joseph Klausner again writes,

The appearance of Jesus during the period of disturbance and confinement which befell Judaea under the Herods and the Roman Procurators, was as inconspicuous an event that the contemporaries of Jesus and of his first disciples hardly noticed it; and by the time that Christianity had become a great and powerful sect the “Sages of the Talmud” were already far removed from the time of Jesus.

Reliable Rabbinical References to Jesus

It has been taught: On the eve of Passover, they hanged Yeshu. And an announcer went out, in front of him, for forty days (saying): “He is going to be stoned because he practiced sorcery and enticed and led Israel astray. Anyone who knows anything in his favor, let him come and plead in his behalf.” But, not having found anything in his favor, they hanged him on the eve of Passover.

The Munich manuscript from about 70 – 100 AD taught “Yeshu the Nazarene.” “Yeshu” translates from Greek to English as “Jesus.” Morris Goldstein notes, “The exaction of the death penalty on the eve of Passover is strong verification that Jesus, the Christ of Christianity, is meant.” This represents an excellent example of a rabbinical reference to Jesus from the first century.

The word “hanged” referred to crucifixion. We know this because both Luke 23:39 and Galatians 3:13 use it this way. But why were the Jewish authorities “Hanging” Jesus rather than stoning him as their law required? The best explanation that has been put forward is that he was killed under the Romans, and crucifixion was the preferred mode of execution for criminals in Christ’s time. The Jews were not allowed the privilege of exacting capital punishment on their citizens under Roman law.

This passage is also significant because of what it does not deny. First, it confirms the Jews were involved in Christ’s death. This is not just some later invention to lame the Jews for Christ’s crucifixion. It demonstrates the Jewish authorities carried out the sentencing, although they did determine the means of execution. The result is a clear affirmation of the death of Christ. Second, the passage affirms Christ performed miracles because he was blamed as a sorcerer. This was, in fact, the same charge leveled against Christ in Mark 3:22 and Matthew 9:34; 12:24. There is an affirmation not only that Christ was a sorcerer, but that he was killed.

The passage also confirms that Jesus had a great following as he was convicted of leading the people astray. The passage also suggests the Jewish leaders were looking to arrest Jesus for some time before the arrest actually occurred. This was also taught in Scripture in John 8:58 – 59. In this passage, the Jewish leaders sought Christ to arrest him before the Passover.

Verdict of The Early Rabbis

View of Jerusalem

There is no indication that the early rabbis thought Christ was a myth or legend, but they all agree he was an actual person. Of course, they considered him a heretic teaching false doctrine and that he deserved the death sentence for blasphemy. But there is no indication they considered him to be only a legend.

Klausner thought the earliest reliable rabbinic sources give us the following facts concerning Christ,

that his name was Yeshu’a (Yeshu) of Nazareth; that he “practiced sorcery” (i.e., performed miracles, as was usual in those days) and beguiled and led Israel astray; that he mocked at the word of the Wise; that he expounded Scripture in the same manner as the Pharisees; that he had five disciples; that he said that he was not come to take aught away from the Law or add to it; that he was hanged (crucified) as a false teacher and beguiler on the eve of the Passover which happened on a Sabbath; and that his disciples healed the sick in his name.

This provides considerable testimony to the historicity of Christ, which is especially important when coming from an unfriendly source. R.T. France concludes,

Uncomplimentary as it is, this is at least, in a distorted way, evidence for the impact Jesus’ miracles and teaching made. The conclusion that it is entirely dependent on Christian claims, and that “Jews in the second century adopted uncritically the Christian assumption that he had really lived” is surely only dictated by a dogmatic skepticism. Such polemic, often using “facts” quite distinct from what Christians believed, is hardly likely to have arisen within less than century around a non-existent figure.

Summary

The ancient rabbinical references to Jesus, coupled with the multiple secular extra-Biblical references to Christ, ably establish him as a historical figure in time. HE is clearly not some mythological figure with no basis but a real person who walked the earth, taught his disciples, established a New Covenant and shook the world’s foundations.

No credence can be given to skeptics who doubt Christ existed, let alone the facts surrounding the Resurrection. The outline of the New Testament can be clearly established through these extra-Biblical sources.

What you do with these facts is up to you.