Herod The Great

There are many villains in world history but few as despicable as Herod the Great. Herod played a pivotal role in the early life of Christ as Herod desperately tried – but ultimately failed – to kill the newborn King of the Jews.

Scriptures depict King Herod as conniving and ruthless, struggling to maintain his power while ruthlessly subduing the Jewish population of Israel. He would stop at nothing to ensure his power, including killing his own children.

Herod killed children less than two years old living in Bethlehem when he heard that the Messiah had been born there from the Magi (the “Wise Men”). Herod wanted to kill the Messiah because he viewed the young Jewish King as a political adversary and a threat to his throne. Herod likely would have killed the Christ child had not the entire family fled to Egypt to escape his wrath. They did not return until they got word that Herod had died.

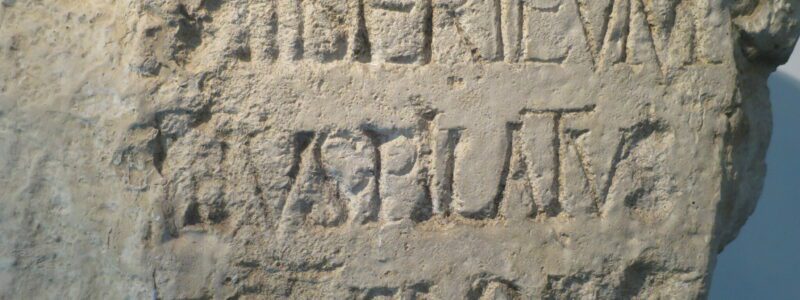

What makes Herod important for our purposes is that he helps us determine when Christ was born. Herod must have died after the birth of Christ – but when exactly did Herod die? Herod’s death date is tied in with the death.

Luke tells us in his gospel (Luke 3:1) that John the Baptist started his ministry 15 years after the death of Tiberius, likely when he was thirty years old in 29 AD. We believe John was likely 30 years old as that is the age when Jewish priests (like John, who was the son of a priest named (Zachariah)) started their ministry (Numbers 4:3). Therefore, if John were 30 years old in 29 AD, he likely was born around 2/1 BC. This makes it likely Christ began his ministry in 29 AD as he was about the same age as John. The Scriptures substantiate this.

A careful review of Paul’s history shows he was converted in 34 AD just after the Crucifixion in 33 AD. So the dating makes sense in a nice sequential order that is substantiated by Scripture, by history provided by the ancient Church Fathers in their pre-Nicene writing, and by non-Christian writers.

The problem is that most Herod biographers place the death of Herod in 4 BC rather than in the more likely 1 BC. The latter date confirms our entire narrative and makes sense when viewed in other historical events in that era.

The Herods

Herod the Great – By Unknown – https://thisblogisratedpgforpropheticguidance.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/herod.jpg, Public Domain, Link

There were many “Herods” in this time period, and since these different rulers are often referred to as simply “Herod,” trying to figure out who is who can be very confusing. Herod the Great was the ruler when Christ was born who was anxious to kill the Jewish King to eliminate him as a ruling competitor. Herod the Great was the second son of Antipater the Idumaean, the founder of the Herodian dynasty.

Idumea was the geographic area between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba known in the Old Testament as the Land of Edom. The man “Edom” was also known as “Esau” and was the brother of the Jewish Patriarch Jacob.

The Edomites are the descendants of Esau and were sworn enemies of the Israelites for several reasons. Trouble between Jacob and Esau started many hundreds of years earlier when Jacob tricked his brother Esau out of his birthright. They eventually reconciled, but history reports their detente was short-lived. The two nations ended up hating each other for several reasons.

Trouble started when the Hebrews led by Moses were traveling from Egypt to the Promised Land in Canaan. Unfortunately, they were not permitted to travel through the land of Edom and had to take a large detour around that country. There was no further record of any interaction between the two countries until several hundred years later when King Saul conquered the Ecomite people in the 11th century B.C… King David defeated them in the 10th century B.C.

But the bad blood between the two countries really started at the time of the conquest of Jerusalem by the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar. Edom took advantage of the conquest of Jerusalem by helping the Babylonians plunder the city. After this time, Jewish congregations would not accept descendants of an Edomite into their midst until the fourth generation. The Edomites earned the eternal enmity of Israel for their treachery against them when they sided with their enemy. There were such bitter feelings on the part of the Jews against Edom that in the Talmudic period, “Edom” became a symbol for the oppressive Roman Empire.

So – imagine the consternation of the Jewish nation after Palestine was conquered by the Romans and an Edomite king (Herod the Great) was placed over Israel. Subsequently, multiple Herods and their relatives ruled the region, including the remnants of the Jewish nation. The Idumeans are never heard of again after the Romans’ brutal conquest of the entire region during the Jewish Wars (66-73 AD and 132-135 AD), as it appears the Roman Legions destroyed their nation.

Antipater the Idumaean

Antipater – the Father of Herod the Great.

Antipater was the founder of the Herodian Dynasty and the father of Herod the Great. Antipater’s past is filled with intrigue and political infighting to achieve ever-increasing power. Antipater initially was loyal to the Roman general Pompey the Great when he conquered Judah in the name of the Roman Republic in 63 AD. Pompey and Julius Caesar then contended for the leadership of the Roman Senate, eventually leading to a civil war.

Pompey was defeated at the Battle of Pharsalus by the much lesser army of Julius Caesar in 48 BC. However, Pompey was able to sneak away from the battlefield dressed as a common citizen and escaped to Egypt, later assassinated. This posed a problem for Antipater as he had sided with the “wrong” ruler who lost the civil war.

Antipater was able to skillfully shift his allegiance to Caesar and probably escape arrest and possible execution. He could ingratiate himself to Caesar further when he took several thousand men and rescued Caesar from Alexandria during a siege. For this “demonstration of valor,” Caesar gave Antipater Roman citizenship, freed him from paying taxes, and gave him many gifts and honors. Finally, but most importantly for our story, Antipater was given rule over Judea.

Antipater’s bad luck continued as his new patron Julius Caesar was assassinated. He then deftly shifted his allegiance once again to Cassius against Mark Antony. In some respects, this was a good pick as Mark Antony eventually committed suicide, But Cassius turned into a brutal dictator demanding huge taxes from Judaea, where Antipater ruled. These taxes were so high that the Romans sold entire cities into slavery to pay them in some instances.

Out of all this mess emerged someone named Malichus, a tax collector who hated Antipater for unclear reasons. Even though Antipater saved his life on several occasions, Malichus plotted to have him killed. After several unsuccessful attempts, Malichus was finally successful when he bribed his cupbearer to poison and kill Antipater.

Herod the Great Starts his Reign

Herod was the second son of Antipater and was born in 72 BC. Herod’s mother was Cypros, a Nabatean Arab princess from Petros in what is now the country of Jordan. Herod’s father was an Edomite whose ancestors had converted to Judaism, and Herod was raised as a Jew. The history of how Edomites converted to Judaism is an interesting sidelight to this whole saga.

John Hyrcanus was a Jewish high priest and Hasmonean (Maccabean) leader born in 164 BC and reigned from 134 to 104 BC. During his reign, he conquered the region of Idumaea (Edom in the Scriptures) and required them to either obey Jewish law or be expelled from the land. Most of the populace then converted to Judaism, and all the men had to be circumcised, giving them a painful introduction to their new religion.

Herod had the good fortune of having his father be a favorite of Julius Caesar after his father rescued Caesar from Alexandria. He was appointed the provincial governor of Galilee in 47 BC when he was about 25 years old. Herod earned the favor of Rome when he was able to extract large taxes from the local citizens and apparently rid the region of bandits. Antipater’s oldest son, Phasael, was governor of Jerusalem.

Herod went on a lucky streak to significantly increase his power and influence. First, the local Roman governor of Syria, Sextus Caesar, recognized Herod for his administrative capacity. Second, Sextus ended up extending Herod’s rule to Samaria and Colesyria (the Baqaa Valley between Lebanon and the Anti-Lebanon mountain ranges in an area now forming part of Syria and Lebanon). This greatly extended Herod’s power and prestige.

Herod’s good fortune continued when in 41 BC, Herod and his older brother Phasael were named tetrarchs by the Roman leader Mark Antony. Then, Hycanus’ nephew Antigonus took the throne from his uncle Hyrcanus II with the help of the Parthians (now modern Iran). Herod feared his leadership was threatened and went to Rome to plead that the Romans government place Hyrcanus II back in power. Herod was unexpectedly appointed King of the Jews by the Roman Senate in the year 40 BC.

Unfortunately, this appointment meant little to Antigonus, who was firmly entrenched in Jerusalem. Herod would have to wrest control of the country from his arch adversary to begin his rule. He started by marrying the granddaughter of Hyrcanus II, Mariamne, to try to secure his claim to the throne and gain some Jewish favor. He already had a wife, Doris, and a young son, Antipater, who were both banished so he could rightfully marry Mariamne.

Antigonus – By Guillaume Rouille – Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, Public Domain, Link

Herod next turned his attention to executing a coup d’etat against Antigonus. Herod and Sosius, the governor of Syria, set out with a large army in 37 BC, successfully captured Jerusalem, and placed the deposed ruler Antigonus under arrest. Herod was anxious to have Antigonus disposed of as he did not want further challenges to the throne. Therefore, Herod sent Antigonus to Mark Antony for execution. From this moment, Herod assumed the unopposed title of King while ending the Hasmonean Dynasty.

Early Threats Against King Herod the Great

Just when things seemed to be doing well for Herod, he faced several plots against his rule. The first plot came from his mother-in-law Alexandra (the mother of Mariamne, from the Hasmonean dynasty). She wanted Herod out of Israel and have the ruler be Hasmonean – she wanted a Jew to rule over Israel. So she went to Egypt and asked Cleopatra – then the wife of Mark Antony – if Aristobulus III could become the High Priest. She demurred and urged Alexandra to leave Judea with Aristobulus III and see Antony personally. When Herod got word of this plot, he ordered the murder of Aristobulus III, and the threat was over.

The second threat occurred when Herod had to choose between Antony and Octavian (later called Augustus Caesar) when there was a civil war between the two. Herod continued with the bad luck of his father and ended up picking the wrong side. He made the unfortunate mistake of picking the losing option – Antony – who decisively lost at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC.

The Battle of Actium, fought off the western coast of Greece, would prove to be one of the most important battles in world history. It would determine the balance of power in Rome for centuries to come and would end the Roman Republic while establishing the first of its many Emperors. The first few Emperors would be fairly decent, but subsequent rulers were despotic, sometimes insane, and usually cared more for their rule than the common people.

Having picked the losing side in this battle, Herod had to convince Octavian that he would be loyal to him. He succeeded as he was allowed to rule over Judea as he saw fit. At this time, Rome was not very interested in the backwater territory of Judea and its rebellious people.

Herod was a despotic ruler and was constantly paranoid about being overthrown. He had considerable contempt regarding the people he ruled, and the people returned the favor. He used secret police to monitor and report the general population’s feelings toward him to head off any future uprisings and arrest rebellious citizens. He would have his opponents removed by force with a personal bodyguard of 2,000 soldiers and then permanently dispose of them.

The Reign of Herod the Great

We know a lot about Herod the Great’s reign over Judea from the historian Josephus among others. Herod can be credited for his massive building projects, which tended to be massive and even awe-inspiring at the time. For example, Herod used the latest technologies and underwater construction techniques to build the harbor at Caesarea. He also built many fortresses (Masada, Herodium, Alexandrium, Hyrcania, and Machaerus) into which he and his family might escape during times of trouble.

Herod angered the religious Jews when he wanted to appeal to the area’s substantial pagan population. He levied a burdensome heavy taxation system, but the construction projects brought employment and opportunities for advancement for the common person.

But Herod could also be insensitive and ignore Jewish law and sensitivities. For example, Herod ordered the construction of a great golden Roman eagle at the entrance of the Temple in Jerusalem, which many religious leaders considered blasphemous. In addition, he would frequently give away large, expensive gifts while emptying the treasury for his many projects.

The Pharisees were unhappy because Herod disregarded many of their demands regarding the Temple’s construction. The Sadducees, who were more associated with the priestly responsibilities of the Temple, were also unhappy with Herod because he replaced their high priests with outsiders from Babylonia and Alexandria.

Herod’s attempt to curry favor with the local Jewish population with building projects in Jerusalem, such as expanding the Temple complex, failed utterly. Instead, he was seen as a despotic ruler more interested in maintaining his kingdom than sustaining his people.

Herod’s Death Date

This site contends that the most likely date for Christ’s Crucifixion was April 3, 33 AD. This assertion is for many reasons as it best lines up with the historical data, astronomical data, and religious customs of the time. Since we believe Christ was about thirty when he started his ministry, which lasted about three years, the usual death date of Herod at 4 BC poses a problem. We know that Christ was born before the death of Herod, but any dates before 4 BC would make Christ much older than 30 at the start of his three-year ministry in 29 AD.

The writings of the Jewish historian Josephus have proven invaluable in understanding the history of the ancient world. It turns out that Josephus was descended from the Hasmonean High Priest Jonathan, who ruled over Judea from 103 – 76 BC. He was a much-revered ruler who helped secure Jewish power and autonomous rule when Rome was busy elsewhere. Josephus was born and raised in Jerusalem and became a Pharisee observing a strict interpretation of the Jewish law against which Christ spoke so harshly.

Josephus – By William Whiston (originally uploaded by The Man in Question on en.wikipedia.org) – https://sites.google.com/site/josephuspaneas/, Public Domain, Link

History of Josephus. Josephus descended from the Hasmonean High Priest Jonathan, who ruled over Judea from 103 to 76 BC. Josephus was born and raised in Jerusalem and became a Pharisee observing a rigorous interpretation of the Jewish law against which Jesus spoke so harshly. Josephus enjoyed early fame when he was chosen to go to Rome to plead with Emperor Nero to release several Jewish priests. Nero had just brutally divorced Octavia and then married Poppaea Sabine, the likely mastermind in Octavia’s gruesome death. So Josephus decides to go to Rome to try to secure the release of several Jewish priests.

Initially, Jewish leaders did not give the enterprise much hope. An earlier delegation from Alexandria led by the very popular Jewish philosopher Philo failed to meet with Emperor Caligula. However, the case with Josephus was different. Josephus changes tactics and gets the help of Nero’s wife, Poppaea. She intervened and was able to obtain the release of the Jewish priests. This made him a hero in Israel just in time for the Roman – Jewish wars to break out. Josephus was drafted into the Jewish military forces as commander of the Galilean soldiers fighting Rome in the Jewish wars of 66 – 73 AD.”

Unfortunately for Josephus and the Jerusalem Jews, the war did not go well for them. While the insurgency had some initial success, the arrival of more Roman soldiers ended their good fortune. The Romans sent three legions, led by Vespasian and his son Titus, who would become Roman Emperors. Josephus and his band of insurgents are fighting the Romans in 67 AD in the Lower Galilee near Yodfat. The town was under siege by a Roman legion, but Josephus could escape to a large nearby cave. Unfortunately, a woman hiding in the cave with this group betrayed its location to the Romans, who offered terms of surrender. The Romans had killed thousands of the Jewish population of Yodfat in fierce fighting, and Josephus recognized his position was hopeless. Josephus wanted to surrender and accept their terms – possibly relying on previous goodwill with Nero – but the others in the cave with him refused.

The Fortress of Masada – By Andrew Shiva / Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

The proud Jewish soldiers knew they would become slaves and instead negotiated a suicide pact. It should also be remembered the preference for suicide over capture was a common Jewish reaction during this revolt with its most dramatic outcome at Masada. When the Roman legion broke through the Jewish defenses at Masada, they found all the men, women, and children were dead from suicide.

Josephus was not pleased with the suicide option. Nevertheless, he tried to use his powers of persuasion, pointing out that “with us (Jews) is it ordained that the body of suicide should be exposed unburied until sunset, although it is thought right to bury even our enemies slain in war.

Suicide was not unambiguously forbidden in any rabbinic literature until many hundred years later. Ultimately, Josephus could not persuade the others to abandon the suicide option but was able to negotiate a means whereby the erstwhile soldiers would perform the suicide. He decided they would kill each other according to lots drawn. Josephus handled the lots, and “whether by fortune or the providence of God” was one of the last two surviving. Josephus was successful in convincing the other survivor to surrender rather than dying. Interestingly, excavations in this area in the 1990s uncovered a mass burial of 30 – 40 people assumed to be Josephus’ companions.

Josephus was taken to the general in the Roman camp. Josephus, ever the conniver, convinced the general he was a Jewish prophet and predicted Vespasian would be emperor. While this might have been a potentially treasonous statement against the ruling emperor (Nero), it gained Josephus special treatment. Apparently, they were far enough from Rome that nobody particularly cared about Nero. Vespasian eventually did become emperor two years later, at which time he freed Josephus and actually granted him relative freedom in the Roman camp.

Josephus served his Roman captors by being an interpreter for Titus (Josephus had learned Latin while in Rome) and became a negotiator with the Jewish garrisons trapped in Jerusalem. Eventually, Jerusalem was captured, 40,000 Jewish fighters were slaughtered, and 1200 women and children were sold into slavery. As a result, Josephus was considered by the Jews to be a traitor to Israel, and Jewish scholars did not popularize his subsequent historical writings for many hundreds of years.

Then, in 71 AD, Josephus was rewarded for his loyalty to Rome and was given Roman citizenship. He was eventually even given comfortable accommodations in conquered Judea and a small pension (because he could never again work among the Jews who would kill him on sight). During this forced retirement, Josephus wrote his two greatest works, The Jewish War in 75 AD and Antiquities of the Jews in 94 AD. These works give a historical account of the Jewish nation for a Roman reader and provide valuable insight into the first century Jewish nation and a history of early Christianity.

The importance of these two works can hardly be overstated as they offer a history that is found nowhere else. They also provide valuable information necessary to establish a chronicle of Christ’s birth and death dates.

Interestingly, this whole scenario led to the modern mathematic problem called the Josephus Permutation. In this exercise, about 40 people are standing in a circle and are counted in fixed intervals. Each time the count determines the next person to be killed, and the problem is to determine where in this circle you stand to be the last man surviving.

Summary

Herod the Great was one of the most important rulers in Jewish and Christian history. However, the Jews hated him as he was an impetuous foreigner whose cruel rule, high taxes, and harsh treatment alienated his people.

The end of Herod’s rule coincided with what historians call the “dark decade” between 4 BC and 6 AD. The decade is dark not so much because of what happened but because of the mystery of what actually did happen.

During this decade, there is so much date confusion among historians that figuring out what happened has become a real challenge. But, of course, this “dark decade” also encompasses the birth date of Christ, who would fundamentally change the world.

One of the most important parts of this interactive puzzle is determining the death date of Herod the Great. This has been a pastime of many historians as it holds the key to help determine when Christ was born.

This will be the topic of our next article.