Charter Schools – Introduction

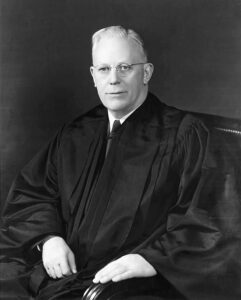

By Harris & Ewing photography firm – Scan of original print courtesy of the en:Harvard Law School Library Legal Portrait Project,[2] whose librarian was gracious enough to confirm this image’s copyright status in e-mail to User:Postdlf., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4352772

Charter Schools

Charter schools recently have been at the forefront concerning the education of America’s children. It is clear to many that some public schools – especially in inner-city minority neighborhoods – have been a dismal failure.

Education in the United States has been a topic of intense political concern since the foundation of the country almost 250 years ago.

Public schools throughout history have enjoyed the support of the community as they provide a means educating children whose parents might have limited education themselves. The education of children was thought important to enable them to become contributing members of society, to hold a job, and to be able to understand the political and social issues of the day.

America has been a religious Christian nation since the foundation of the country. It seemed self-evidence that children would need to be able to read in order to understand Scriptures for themselves and not rely upon the interpretation of others. This concern resulted in the early school readers which included quotations and morality lessons from the Bible to help children apply what they read.

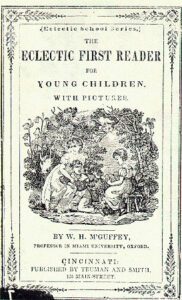

McGuffey Readers

The McGuffey Readers were a series of books for children in the first through sixth grades which were used as textbooks in American schools for about seventy years, and are still used today in some private schools. It is thought that about 120 million of these “readers” were sold between 1836 and 1960, and they have continued to sell at a rate of about 30,000 copies a year.

By William Holmes McGuffey – Originally published: McGuffey’s First Eclectic Reader by William Holmes McGuffey, 1841Source site: http://www.lib.muohio.edu/my/pix/reader.htmlSource URL: http://www.lib.muohio.edu/my/pix/reader.GIF, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17815322

The readers first came into existence as a result of a small Cincinnati publishing firm which asked McGuffey for a series of four graded readers for primary school children. Interestingly, he had been recommended to the publisher by Harriet Beecher Stowe who would achieve fame and infamy for her publication of the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The first four were completed in 1836 with two more editions for the fifth and sixth grades completed by his brother during the 1840s. The more advanced readers not only contained Biblical stories, but also presented English and American writers and politicians such as Lord Byron, John Milton, and Daniel Webster.

Unfortunately, not all children enjoyed the educational opportunities given to children of that era. Schools were (and continue to be) funded largely from the property taxes of the community in which they are located leading to disparities in school quality. Schools located in wealthy communities enjoyed much greater financial support than those located in poorer ones. Frequently, this disparity in funding resulted in much greater educational opportunities in richer neighborhoods.

Separate But Equal

Image by Denise McQuillen from Pixabay

Schools were racially segregated with Black and White students going to their own schools. Many in each community felt Blacks would be better taught by adults from their own ethnic background who would better understand their history and culture – White teachers were often not welcome. While their socialization might have been better served, their educational opportunities were clearly deficient as the drop-out rate from inner-city high schools and their poor academic achievements clearly testify.

“Separate but equal” was found not to be a tenable educational philosophy and ruled illegal by the Brown V. Board of Education decision in 1994. The Supreme Court proclaimed by a unanimous decision that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” and therefore violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution.

What was missing in this monumental decision was how to implement the integration of Black and White students to ensure equal opportunity for an education. Integration met with determined resistance from political interests throughout the South including Arkansas. The governor Orval Faubus called out the state’s National Guard to prohibit black students’ entry to Little Rock Central High School. President Eisenhower then responded by deploying elements of the 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and federalized Arkansas’s National Guard to impose segregation on the high school.

Race-Integration Busing

Many school districts throughout the country were slow to fully apply integration and more lawsuits ensued. While the decision of the Supreme Court in 1954 that the so-called “separate but equal” educational policy was unconstitutional, it failed to provide a means for ensuring integration.

This lead to the 1971 Supreme Court decision Swann vs. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education that forced school busing could be used as an integration tool to achieve racial school balance. The court further ruled that racial balance had to be obtained even if it meant the redrawing of school boundaries and the use of busing. The racial composition of individual schools was mandated to represent the racial composition of the larger community. The expanse of that “large community” was left open for courts to decide and ultimately resulted in endless lawsuits.

These lawsuits represented the lack of public support for forced integration through busing. Louisville, Kentucky was one of the focal points of this protest which persisted throughout the country. In 1975, the district was forced to adopt a school busing program resulting in 1,000 protestors showing up to protest the decision. A few days later, about 10,000 whites – mostly teenagers – rallied at the high schools and fought with police trying to break up the crowds.

During these fights, police cars were vandalized, 200 were arrested, and many people were hurt. Demonstrations persisted even though further rallies were banned by Louisville’s mayor. The Kentucky Governor Julian Carrol sent 1800 members of the National Guard to be present on every school bus to ensure order.

Furthermore, Congressional opposition to school busing continued. Delaware senator Joe Biden noted,

I don’t feel responsible for the sins of my father and grandfather.

Biden also noted that busing was,

a literal train wreck.

Joe Biden and the other Senator from Delaware at the time, William Roth, attempted to get support for a Constitutional Amendment that “prevented judges from ordering wider busing to achieve actually-integrated districts.”

Another lawsuit involved a federal judge in Detroit who argued that busing of children – including kindergarten children – to suburban schools did not seem to be too much to ask. He noted,

Transportation of kindergarten children for upwards of forty-five minutes, one-way, does not appear unreasonable, harmful, or unsafe in any way.

His decision was met with pushback from both the White and Black communities, neither of which fully supported having children in buses for one-to-two hours a day in order to achieve integration that had limited effects on academic achievement. This resistance led to further lawsuits with the resulting Supreme Court case, Milliken v. Bradley which imposed limits on busing. The issue was whether busing could be ordered between cities and suburbs to achieve school racial integration. The court essentially found that federal courts did not have the authority to order inter-district busing of children under most circumstances.

Academic Failure of School Busing

The busing of students to achieve racial balance was predicated upon the assumption that it would improve the academic performance of poor inner-city students.

In 1978, a proponent of busing, Nancy St. John, studied 100 cases of urban busing and found no cases in which there was a significant black academic improvement. However, she did find many cases where race relations had suffered due to busing. Those in forced integration schools had worse relations with the opposite race than those in non-integrated schools.

This finding was substantiated by a 1992 study led by Harvard University Gary Orfield, who reported that black and Hispanic students lacked “even modest overall improvement” as a result of court-ordered busing.

Economist Thomas Sowell, who is himself African-American, noted that the whole concept upon which forced integration was based was flawed. He noted,

When Chief Justice Warren said that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” he was within walking distance of an all-black public high school that sent a higher percentage of its graduates on to college than any white public high school in Washington. As far back as 1899, that school’s students scored higher on tests than two of the city’s three white academic public high schools.

An Alternative – School Choice and Charter Schools

School Choice to improve academic performance of poor inner-city students.

Eventually, busing became largely a relic of the past whose success was mitigated by lack of improvement in integrated Black schools, and White migration out of predominantly Black school districts.

The appeal of forced busing was further diminished when 60 Minutes reported that many members of Congress who supported forced integration such as Senator Edward Kennedy, George McGovern, Thurgood Marshall, Phil Hart, Ben Bradlee, Senator Birch Bayh, Tom Wicker, Philip Geyelin, and Donald Fraser all sent their children to private schools. Even though these officials mandated forced busing for others, they had sufficient privilege to place their children into private schools.

Gradually, forced busing caused parents to consider other choices for their children, just as did many government officials who supported forced integration. The idea that low-income parents could decide where their children went to school by sending their children to private schools if the local school was unsatisfactory.

Extending choice to parents could be done through vouchers which might pay for at least part of the tuition at private and Catholic parochial schools.

There were also magnet schools, homeschooling, tuition tax credits, among other possibilities. The forced integration of unwilling parents led them to consider other educational choices for their children.

Suddenly, the government schools were facing competition.

One particularly interesting aspect of these emerging private schools is they allowed experimentation – trying to find the best way to educate needy students. Parents like being free from the rigidities of government schools and found they could receive the same amount of instruction in much less time.

Not all these private schools turned out to be successful, just like many public schools were not successful. But private charter schools located in Black and Hispanic communities achieved educational results far above that achieved by most public schools but sometimes even better than most schools in affluent communities.

Conflict

The private charter school might have had a happy ending with school choice becoming a possible choice for poor students attending underachieving schools.

But such is not the case.

Even the most successful private schools have been bitterly attacked by certain interest groups such as teachers’ unions, politicians, civil rights establishment, and others. The charter school system was wildly successful in New York City where there are more than 50,000 children on waiting lists to attend. Yet New York’s mayor has announced an end to the expansion of charter schools and threatened further restrictions.

A similar situation has occurred in California, as well as many school districts in-between.

With growing political threats to charter schools, it is important to become aware of the statistics which will be evaluated here. The stakes could hardly be higher for poor and minority students who are trying to break free from poverty but are blocked by many obstacles. One of their greatest obstacles is the failure of government schools to provide an education – many who do graduate from high school are functionally illiterate and were ill-served by their educational experience.

Of course, there are many reasons for the failure of most government schools in minority neighborhoods. The students face poor living conditions, often a difficult family situation, and lack of support from their friends, and temptations from their associates to become involved in gangs and the drug culture.

All children can learn to become successful in our ever more complex technological world. It is the responsibility of family and schools to educate children to take advantage of these changes. But the education gap between the Black and White communities still exists, and communities need every tool available to address this persistent problem.

The charter school is one of those tools.

Summary regarding Charter Schools

Inner-city schools are failing to provide an adequate education to their students – this will be further examined in subsequent articles.

Many “solutions” have been offered, including pre-school education such as the Head Start program, forced busing to better schools to achieve racial integration, private charter schools, parochial schools, homeschooling to name a few. Each of these has its proponents and detractors, and each of these solutions is not homogeneously applied in every instance – some charter schools are definitely better than others.

Parents have learned, however, that government schools have an ever-increasing amount of non-educational activity taking inordinate amounts of time. This means homeschoolers are able to do in a morning what would take a whole day in government schools.

Charter schools are competitive, not only with government schools but with each other. If they do not perform, they will start losing students and go out of business. Those that succeed will expand their school system and start replacing government schools. The latter has not gone unnoticed by teachers’ unions and government officials who benefit from contributions from these unions. Government schools that lose students lose money, but they can use their political clout rather than competitive edge to affect policy.

So what is the truth – do charter schools help educate even the most difficult students in the most difficult home and social situations, or do they only steal the best students from government schools.

References

Frum, David(2000). How We Got Here: The ’70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. pp. 252–264. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

Orfield, Gary; Franklin Monfort (1992). Status of School Desegregation: The Next Generation. Alexandria, VA: National School Boards Association. ISBN 978-0-88364-174-3.

‘Thomas Sowell (June 30, 2015) Supreme Court Disasters, Jewish World Review, accessed 22 September 2019

Thomas Sowell, Charter Schools, and their Enemies, 2020