Charitable Giving

By Ddokhanian – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Charitable giving has been part of the American narrative since its founding. The average citizen of colonial America supported the church, helped build hospitals, libraries, and supported higher education.

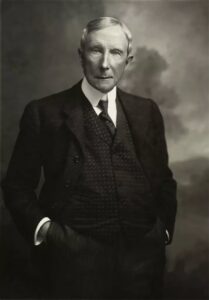

Charitable giving has also been important to some of the richest Americans who ever lived. Rockefeller was one of those Americans.

John D. Rockefeller was one of the richest men who have ever lived.

He is reported to have said, “God gave me my money” in 1905. This quotation has been used to show the callousness and insensitivity of men of great wealth. It sounds like justification for his hoarding such wealth while others in the country were suffering from want and even starvation. However, this is precisely the opposite of what Rockefeller was trying to say.

But this was only the beginning of his quote,

God gave me my money. I believe the power to make money is a gift from God … to be developed and used to the best of our ability for the good of mankind. Having been endowed with the gift I possess, I believe it is my duty to make money and still more money and to use the money I make for the good of my fellow man according to the dictates of my conscience.

Rockefeller was not abusing God’s name in a vain attempt to justify his wealth. He believed God made him rich so that he might be a good steward of God’s blessings on earth. Rockefeller believed the money he made did not belong to him, but rather it was a gift from God. He additionally believed that if he was not responsible for the money entrusted to him by God, God would withdraw his generosity.

Rockefeller’s Early Life

Rockefeller’s relationship with money was established early in life. When he was ten years old, he made a loan of $50 at 7 percent interest to a neighbor – a very large sum of money in those days. He was amazed to learn that he was given $53.50 at the end of a year. The benefit of interest was rather like a revelation for him noting,

From that time onward I determined to make money work for me.”

He kept a ledger concerning his donations, and by the age of sixteen was giving to a wide variety of charities and causes. He was also a great fundraiser, finding his abilities to generate large amounts of capital much greater than his ability to provide for himself – at the time. He set out to save his church from eviction at twenty-one years old by donating his own money along with those of others. He was eventually able to raise $2,000 (about $45,000 in today’s money) for the cause – and the church was saved.

He would go on to found the Standard Oil Company and saw his wealth explode. He was concerned he would not be able to donate his money responsibly and hired Frederick T. Gates. Gates developed “scientific philanthropy” focusing charitable giving in ways to have the greatest impact creating the most benefit for others. The founding of the University of Chicago is an example of this scientific philanthropy. He believed his way of giving money in a predetermined fashion rather than on a whim would be the best way to serve as a steward of “God’s money” for the greatest good.

Rockefeller blended theology and finance today believing that without prosperity, large-scale charity becomes impossible in what is known as the Rockefeller Hypothesis.

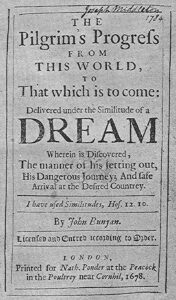

Pilgrim’s Progress

John Bunyon’s famous work – By The original uploader was Drboisclair at English Wikipedia. – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons., Public Domain, Link

The Rockefeller Hypothesis is summarized in John Bunyon’s Pilgrim’s Progress written in 1678. In this novel, Old Honest poses a riddle to the innkeeper named Gaius,

A man there was, though some did not count him made

the more he cast away, the more he had.

Gaius interprets the riddle by noting,

He that bestows his goods upon the poor

Shall have as much again, and ten times more.

If Bunyon is right, charity is as important to the giver as it is to the receiver – maybe even more. This might argue if charity causes prosperity, then selfishness causes poverty. The consequences of uncharity across the world – and certainly in America – are more corrosive than might be imagined.

Bunyon’s famous 17th-century novel invoked the Christian principle that those who give are rewarded. This reward may not be in financial resources but in other ways such as personal satisfaction, self-actualization, happiness, and becoming a solution rather than a victim or a problem.

Social Theory

Modern social theorists confirm the association between charity and prosperity. George Gilder believes that a charitable society in which people are generous with each other is founded upon people giving to others without expectation of immediate or guaranteed return. He notes how capitalism looks like a “good society” as the investor has a certain amount of faith in the economic system. He believes the economic system will pay a positive return. These investment “gifts” are given with faith in that there is not usually a predetermined return on the investment. In his view, charity stimulates prosperity in much the same way.

Thorstein Veblen has a similar theory perhaps expressed in a more understandable manner. He believes charity encourages people to become industrious and notes,

[T]he residue of the religious life – the sense of communion with the environment, or with the generic life process – as well as the impulse of charity or of sociability, act in a pervasive way to shape men’s habits of thought for the economic purpose.

The idea is that people may work harder to be charitable – so that they have more money to give away. It may well be that working hard and charity go together – it is hard to be charitable if you do not have an income.

Benefits from the charity also relate to the personal transformation of the giver. The giver becomes more effective, happier, healthier, and more successful.

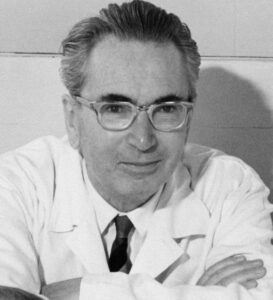

By Prof. Dr. Franz Vesely, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, Link

Victor Frankl was an Austrian neurologist and psychologist who was a Holocaust survivor having survived multiple concentration camps including Auschwitz. He was the founder of logotherapy meaning therapy through meaning – a meaning-centered school of psychotherapy. He is the author of multiple books, his most noted being Man’s Search for Meaning based upon his experiences in Nazi concentration camps.

Frankl made the critical observation that when prisoners found meaning in their lives, they tended to survive more. He also found this to be true in his psychiatric patients. Once his patients dedicated themselves to a cause they experience meaning in their lives which translated into a greater will to survive along with increased personal effectiveness.

One such meaning is often some form of charity whether monetary, time charity, working for a cause or a people. Having meaning to life provides improved happiness, health, and survival.

These theories all suggest that charity should have a positive effect on a person’s well-being. This should translate into improved financial prosperity, personal satisfaction, job performance, health, happiness, and enough people – national prosperity. Charitable giving also provides connections to similar minded people improving the “social net.”

Religious Explanations

Every religious tradition invokes the spirit of charity. Proverbs notes, “One man gives freely, yet gains even more; another withholds unduly but comes to poverty.”

The English theologian Matthew Henry wrote an important Bible commentary and in this commentary interpreted Proverbs as, “God blesses the giving hand, and so makes it a getting hand.”

Christ noted that it is better to give than to receive.

Data Supporting the Rockefeller Hypothesis for Individuals

Poverty – Image by Sri Harsha Gera from Pixabay

Psychiatry often relies upon observational data rather than the empirical. Probably the greatest criticism of Freud, for example, is that his entire theory was developed without empirical data for support. Even though a theory may seem inherently obvious and even have success as a therapeutic tool, the entire theory itself may be based upon false assumptions.

There is no doubt that empirical evidence supports the positive correlation between charity and prosperity. While Americans of all income classes are generous compared to other societies, this generosity is positively correlated with income; the more prosperous a person becomes over time, the greater his giving increases.

For example, an American earning $100,000 in 2000 was ten percent more likely to give a larger percentage of its household income than an average earner making between $30,000 and $50,000. The richer person was more likely to volunteer and give in other nonfinancial ways as well.

A counter-argument is that those who make more money have more disposable income and less pressure on their lives than people less up the financial ladder. Studies have tried to control for many variables including education, age, religion, politics, sex, and race. The only difference is that one person volunteers their time and money annually while the other does not. The data indicate that the charitable person will earn, on average, about $14,000 more per year than the other.

The data is clear concerning an association between charity and prosperity – the question is whether there is a causality. Said another way, does charity produce prosperity. Conventional wisdom says that income comes first, and then people become more charitable.

The data are analyzed using a least-squares regression analysis taking into consideration multiple possible confounding factors such as educational attainment, age, race, and host of others.

The data show that charity and prosperity tend to reinforce each other. This means that giving more to charity causally increases prosperity while prosperity causally increases charity. The amount of this association was rather surprising: a dollar given to charity is associated with $4.35 increased income. At the same time, each increased dollar in income increased charity by $0.14.

This seems to support the impression that poor people who give a significant portion of their income to charity tend to experience increased upward mobility in income. This may also help to explain why persons who are disciplined enough to contribute to charity have good work habits and orientation to opportunity rather than depending upon government handouts. In short, they are better able to escape from poverty.

Benefits of Charitable Giving for Income

- A family in 2000 earning $100,000 was ten percent more likely to give to charity than a lower-middle-income family,

- Those who do tithe tend to be in better financial shape than those who don’t. Nearly one in three others are debt-free vs. 13 percent of non-tithers,

- Those who tithe are 40 percent less likely to owe more than $50,000,

- Those who tithe are only half as likely to be overdue on their credit cards,

- The ten million people who tithe in America done more than $50 billion annually to charity

- 77 percent of people who tithe give more than 10 percent of their income to charity, with 9 percent of those who tithe giving 20 percent or more

Image by Brian Bracher from Pixabay

The advantages of giving more do not stop with the individual, however, because the economy as a whole is improved as well. Charitable giving and the GDP (gross domestic product) of the country tend to move together. GDP per person in America has risen over the past fifty years by about 50 percent; charitable giving per person has risen by about 190 percent.

Benefits of Charitable Giving for National Gross Domestic Product

Analysis reveals that charitable giving and GDP are mutually inclusive – they reinforce each other. In 2004, an extra income of $100 per American was associated with an increase of $1.47 in charitable giving per person. Additionally, a one percent increase in charitable giving – about $1.9 billion – increased the GDP by about $36 billion. (The causal effect is substantiated through statistical analysis using data provided by the Statistical Abstract of the United States with giving data provided by the Indiana Center on Philanthropy).

Put another way, consider the financial effects if charitable giving were cut in half. This would produce a deficit of $95 billion fewer dollars per year producing a significant reduction in income for charitable causes including social welfare, health, education, the arts, religious faith, and the environment among many others. But what is particularly interesting is that such a reduction in giving would lead to a reduction of about $1.8 trillion in national income – or about 15 percent of American GDP.

America would be a significantly poorer nation today without charitable giving.

Connection Between Charity, Happiness, and Health

Image by Nattanan Kanchanaprat from Pixabay

There is a causal association between charity and financial success that likely has to do with changes in attitudinal changes in the giver.

But financial success while important does not necessarily lead to happiness and self-actualization. In other words, “money can’t buy happiness.” Most of us have been taught that axiom since childhood and frequently see it played out in the lives of Hollywood celebrities.

Giving also is associated with increased happiness and even health. Those who give money to charities are 43 percent more likely to say they are “very happy” than those who do not. Those who do not give to charity are 3.5 times more likely than givers to say they are “not happy at all.”

Volunteers who give their time to charity rather than money are 42 percent more likely to say they are very happy.

Those who are givers are 25 percent more likely to say their health is excellent or very good; alternatively, non-givers are about twice as likely to say they have only poor or faith healthy. The data also holds for those who give blood rather than their time or money. Approximately 15 percent of Americans donate blood at least once a year. These people are 27 percent more likely than nondonors to say they are very happy, and 33 percent more likely to say they are in good health.

The skeptic might say that only healthy people can give blood so there is an inherent bias in these statistics. However, among people who say their health is excellent (about one-third of the population, who are identical in other potentially confounding factors including education, income, age, sex, race, religion, and political views. The healthy person who gives blood will be 9 percent more likely to say they are happy than the nondonor.

The elderly who volunteer have a 40 percent lower probability of dying over the next year as opposed to those of the same age and health who do not volunteer. These benefits are even greater for volunteers who also participate in religious activities.

Causal Associations Among Charity, Happiness, and Health

Jeff had all the money he would ever need – Image by PublicDomainPictures from Pixabay

There is a causal association between being charitable and the achievement of happiness and health. One particular study of American Presbyterians by the University of Massachusetts Medical School evaluated the effect of volunteering on mental health outcomes. They found that those who volunteered were more likely to experience health and happiness benefits than those who were only receivers.

They also found that predictors of being a helper included prayer activities and high church involvement.

The author of this study explained the findings by noting,

when you open your heart to other people to listen and care about them, it changes the way you look at the world and you’re happier.

Other studies have shown a causal association between charitable giving (whether time, treasure or talent) and depression relief, improved immune function, lower blood pressure, improved symptoms of asthma, chronic pain, arthritis, indigestion, among others.

The causal relationship is further substantiated by the finding that the more a person volunteers, the greater these health and happiness advantages.

Freedom and Charity

Image by Daniel Reche from Pixabay

It was a principle of the Founding Fathers that only a virtuous people could be governed by a representative government; a selfish people could never be government as they would always vote to take away from others rather than act to contribute to society. Of course, there is an amount that needs to be contributed by the general population for the public good, but this must never be greater than that which is necessary.

Taking money from the productive population in excess of what is needed for the public good for expenses such as building infrastructure, police, fire protection, national defense along with a few other narrowly defined expenses endangers the freedom of everybody. A government that is powerful enough to take more than what is needed for the public good is capable of taking everything.

Excessive taxation of productive individuals leads to a disincentive to remain productive. Excessive taxation also leaves less for charitable giving. The government – rather than the people – determine who receives the charity and more importantly, who does not. Tyrannical governments pick the losers and winners in society with the winners most likely being their political supporters.

Alexis de Tocqueville in his epic tome, Democracy in America, asserted that American democracy depended on politicians being held accountable to an informed electorate. The informed electorate is involved in community organizations, charities, and other causes they wish to support.

The economist Peter L. Berger wrote in his 1977 book To Empower People: From State to Civil Society, applied de Tocqueville’s assertion that people, not governments, were best positioned to make decisions regarding their charitable giving. The government needs to empower its citizens to promote charitable organizations according to perceived local needs. The authors were particularly concerned that an over-reaching government choosing which charities are important would assume the traditional role of churches in American society.

The danger today is not that churches or any one church will take over the state. The much more real danger is that the state will take over the functions of the church.

The political climate of 1977 saw the expansion of the “welfare state” by Jimmy Carter, while the Christian Right had not yet emerged as a coherent political force to advocate for the rights of the individual or the church. Public school children were being forcibly bused out of their communities for the sole purpose of complying with racial mixing criteria imposed by bureaucrats and judges. America – at least for a short time – learned the hard lesson of an over-reaching government forcing its ideals upon its citizens.

Today many policymakers advocate “faith-based organizations” for the distributions of social services rather than the government. Society learned how private giving is essential to the protection of a free society and the exercise of our democratic rights.

Recently, however, a growing number of younger individuals who are not familiar with the excesses of an all-powerful government, are promoting the resumption of a welfare state. We hope America will not need to relearn the hard lesson that a government that is too powerful can remove your freedoms much more quickly than a decentralized government closer to the people.

Evidence Supporting Charitable Giving

There is significant empirical evidence supporting the value of charitable giving. Those who give are far more likely to be active in the political process those than who do not give. Givers follow public affairs more closely than those who do not and are more likely to vote and contact their elected officials.

Summary

Charitable giving is important for those giving charity, as well as those receiving the donations.

Charitable giving contributes to the happiness, sense of self-worth, and physical health of the giver. Counter-intuitively, charitable giving is also associated with increasing personal wealth. More specifically, poor people who give more to charity have increased levels of upward mobility.

Charitable giving is associated with increased personal fiscal responsibility and encourages empathy for those less fortunate.

Individual charity decreases when the government increases taxation in the mistaken notion that “government knows best.” Increased government taxation leads to reduced charitable giving. When governments forcibly extract ever-increasing amounts of taxes from its citizens, there is less available for personal giving.

It goes without saying that the government is much less efficient and much more wasteful of heir money than secular charities.

References

Brooks, Arthur C., Who Really Cares: America’s Charity Divide: Who Gives, Who Doesn’t, and Why It Matters