Historicity of Biblical People – Judah Kings Part One

The historicity of Biblical people has been confirmed by archaeological research over the past few decades. These people are listed in the Biblical Archaeology Society online archives and provide some confirmation of Biblical historicity in general.

Some confirmed biblical people through multiple archaeological findings, while others are part of a larger historical narrative (such as Egyptian pharaohs and secular historical knowledge).

Hebrew Kings

King David

Many liberal historians have doubted the existence of the Hebrew kings, preferring to reference them as mythological. The general explanation suggests that after the Israelis were held captive in Babylon for many years, some returned to Jerusalem to rebuild the city. This repair included rebuilding the walls surrounding the city to keep it protected against foreign invasion. This required extensive rebuilding over many decades, requiring the citizenry to undergo significant hardship leading them to invent a historical mythology of ancient kings much more successful against their enemies.

Tel Dan Stele with “House of David inscription” – By Oren Rozen – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

King David was one of the more popular of these ancient kings, holding together an extensive kingdom that mostly successfully fought against its predatory neighbors and followed the dictates of God. The problem was that the name “David” never appeared on any archaeological evidence leading many to doubt his existence. There was even more doubt that such a historical figure could approach the historical “King” David alluded to in Scripture.

This narrative changed in 1993 when a chance discovery in an excavation led by Avraham Biran found an inscription on a basalt stone. This stone was used in the lower part of a wall in Dan in northern Israel. It was a victory stone commission by a non-Israeli king mentioning victory. The stone mentioned “the king of Israel” and the “house of David.” While it is not clear whether the foreign king’s claim to victory is historically accurate, it nonetheless confirms the existence of King David.

Hezekiah

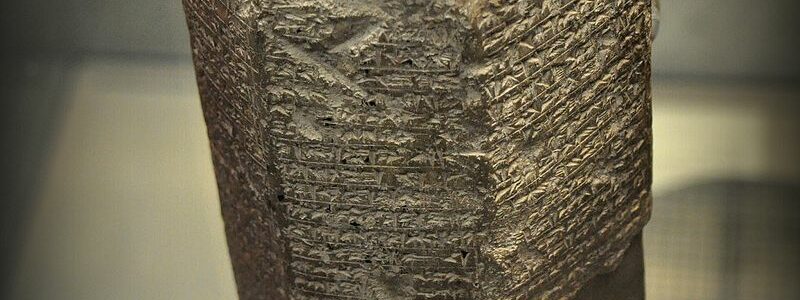

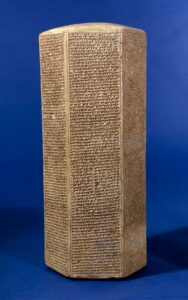

Sennacherib Prism

Hezekiah is another Israelite king with an extensive Old Testament history. Scripture places Hezekiah in the eighth century who “did what was right in the sighs of the Lord just as ancestor David had done) (2 Kings 18:3; 2 Chronicles 29:2).

Hebekiah is credited with building a tunnel called Hezekiah’s Tunnel to supply water to Israel. This feat would provide Jerusalem with water during the war when the enemy might be under siege. Jerusalem could withstand the siege of the Assyrian ruler Sennacherib partially due to the water provided by this tunnel into the Pool of Siloam.

Hezekiah is recorded in an inscription known as Sennacherib’s prism. He claims to have shut up Hezekiah in Jerusalem “like a bird in a cage” but does not claim to have conquered Jerusalem, confirming the Biblical narrative.

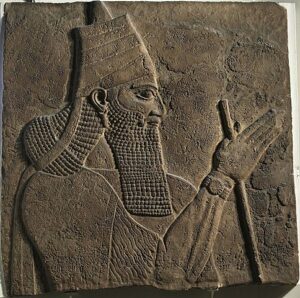

There are also many reliefs of Sennacherib now housed at the British Museum during his capture of Lachish – a neighboring city of Jerusalem.

Sennacherib saved Hezekiah and Jerusalem itself from destruction – such would not be the case with our next king: Hoshea.

Ahaz

King Ahaz had a problem. A coalition of his enemies was forming to threaten his southern Kindom of Judah. This coalition consisted of the ruler of the northern Kingdom of Israel (Pekah) and Aram (an ancient region in northern Syria) under Rezin. This coalition had as its main objective the plan to oppose the powerful ruler of Assyria, Tiglath-Pileser III.

The prophet Isaiah counseled against joining this coalition and insisted the King turn to God for protection rather than foreign allies. Ahaz ignores the prophet and instead joins the Assyrians in opposing this new coalition.

Tiglath-Pilesar won decisively against this insurgency, defeating Rezin and Pekah. According to 2 Kings 16:9, the population of Aram was deported into Assyria, while Rezin was executed. Tiglath-Pilesar deported the surviving population of the northern kingdom to Assyria. These deported people became known as the “Lost Ten Tribes of Israel.”

Ahaz considered himself out of trouble with this coalition destroyed. Ahaz furnished tribute to the Assyrians, which was strongly opposed by Isaiah. Meanwhile, Ahaz wanted to ingratiate himself with Tiglath-Pilesar by wearing homage to him and his gods. He made a copy of an altar he observed while in Assyria and placed it in the Temple. This altar then became an object of worship

His government is considered by historians to have been disastrous for the religious state of the country. It would require long years of reformation by his son, Hezekiah, to return the kingdom to God.

The historicity of Ahaz’s reign is attested in several remarkable bullae. One bulla came to light in the mid-1990s bearing the imprint of the papyrus it once sealed and the double string which held everything together. There is an inscription on the Bulla reading, “Belonging to Ahaz (son of) Yeholam, King of Juday.” Most scholars believe this bulla to be authentic as it was likely burnt in a fire.

There is another scaraboid seal from the 8th century BC also mentioning Ahaz. Its inscription reads, “Belonging to Ushna servant of Ahaz.” The seal is currently part of Yale University’s collection of ancient seals.

Another artifact confirming the historicity of Ahaz comes from Tiglath-Pilesar himself. His annals mention tributes and payments he received from King Ahaz. Finally, in 2015, an archaeologist discovered a bulla belonging to Hezekiah, the biblical son of Ahaz. This bulla reads, “Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz King of Judah.” This latter bulla dates to between 272 and 698 BC.

Hezekiah

Cuneiform writings have Sennacherib, the ruler of Assyria, boasting that,

I laid waste the large district of Judah and made the overbearing and proud Hezekiah, its king, bow in submission. I laid siege to 46 of his strong cities: … and conquered them.

The Scripture tells of the struggle Jerusalem had with this ancient king,

King Sennacherib of Assyria invaded Judah and encamped around the fortified towns. (2 Chronicles 32:1)

By Lior Golgher – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1830495

Scripture also confirms the boast Sennacherib made that he conquered all the fortified towns of Judah. But both the Scriptural and Sennacherib’s accounts are consistent in that Jerusalem was never captured. In the Bible, Jerusalem was saved by a miracle; no explanation is provided by the Assyrians.

Some evidence of the destruction of the many “fortified cities” has also been provided by recent archaeological exploration. One of these is the Iron Age city of Tel Halif which was likely destroyed by Sennacherib.

The destruction was apparently swift and intense. The fire was so hot that the mudbricks of several houses were baked, with a thick layer of ash covering much of the destruction.

Multiple arrowheads, sling stones, and weapons discovered at the site provided further proof of the destruction. The ancient name of the site was Rimmon meaning pomegranate.

Hezekiah is one of the righteous kinds of the Southern kingdom. He is accredited with purifying the Temple, purging its idols, and reforming the priesthood. Interestingly, he destroyed the “high places” and the “bronze serpent” made by Moses. The latter apparently became an object of idol worship rather than reverenced as being a symbol of Christ.

Hezekiah was also a warrior king defeating the Philistines “as far as Gaza and its territory.” He resumed the Passover which stopped during the disastrous reign of his father, Ahaz.

Extra-Biblical records confirm the historicity of Hezekiah. The Anchor Bible Dictionary (1992) notes that,

Historiographically, his reign is noteworthy for the convergence of a variety of biblical sources and diverse extrabiblical evidence often bearing on the same events. Significant data concerning Hezekiah appear in the Deuteronomistic History, the Chronicler, Isaiah, Assyrian annals and reliefs, Israelite epigraphy, and increasingly, stratigraphy,

Eilat Mazar discovered a bulla (or stamp) bearing the inscription in ancient Hebrew script that is translated as saying: “Belonging to Hezekiah [son of] Ahaz king of Judah.”

Hoshea

King Hoshea was the last king of the northern ten tribes of ancient Israel. An ancient seal bearing the inscription “Belonging to Abdi, servant of Hoshea, has been found.

The backstory relating to Hoshea provides insight into the problematic specialty of archaeology. This seal was in a private collection but came to light when auctioned at Sotheby’s. The seal bears the image of a man with a long kilt and a short wig holding a papyrus scepter. Only one Hebrew king was Hoshea, their final king before being conquered by the Assyrians and taken captive.

The seal’s writing in paleo Hebrew fits in with 8th-century BC Hebrew writing – the time of King Hoshea, according to epigrapher Andre Lemaire.

Tiglath-Pileser

Hoshea had a long and complicated interaction with the Assyrians. Austen Henry Layard discovered a large pavement stone that discussed the interactions between Hoshea and Tiglath-Pilesar III – the ruler of Assyria. Layard then made paper squeezes of this inscription which, unfortunately, were lost. However, the inscription was also copied by George Smith and is available for translation. The summary Inscription reads,

The land of Bit-Humria [literally Omri-Land or Israel] … all of its people […to] Assyria I carried off. Pekah, their king, [I/they killed … and Hoshea [as king] I appointed over them.

This affirms the historicity of Hoshea as well as the Biblical narrative concerning him. 2 Kings 15:29-30 reads,

In the days of Pekah king of Israel, Tiglath-Pileser king of Assyria came and captured Ijon, Abel-beth-maacah, Janoah, Kedesh, Hazor, Gilead, and Galilee, all the land of Naphtali, and he carried the people captive to Assyria. Then Hoshea the son of Elah made a conspiracy against Pekah the son of Remalia and struck him down and put him to death and reigned in his place, in the twentieth year of Jotham the son of Ussiah.

Hoshea promised to give allegiance to Assyria in exchange for helping him capture the throne. He remained a faithful Assyrian vassal throughout Tiglath-Pileser’s reign. Hoshea is also mentioned in another inscription where Tiglath-Pileser takes credit for appointing him king on the throne as his vassal.

Hoshea’s story turns dark when a new king comes to power in Assyria. Scripture notes that Hoshea initially paid Shalmaneser tribute but made the unfortunate choice of changing his loyalty to Egypt. (2 Kings 17:4). Shalmaneser from Assyria was not pleased and laid siege to Samaria for three years. He eventually conquered the city and took the Israelite king as a prisoner. Assyria would then populate Samaria with people from other conquered territories who became known as Samaritans.

Summary

Archaeologists are confirming the historicity of the Biblical account with every passing year. While most archaeologists doubted even the existence of David, for example, he has now been proven to be a king in ancient Israel. Whole civilizations – such as the Hittites – were doubted to exist, but archaeological digs have uncovered their civilization.

The amount of ancient Scripture critics can consider myth is becoming smaller every year as archaeology confirms the ancient evidence.

The next post will continue with ancient