Paul’s Conversion Date

Bible – Image by Free-Photos from Pixabay

Paul’s conversion date has been a topic of intense academic study for many decades. As a result, a historical narrative has been painstakingly assembled to include many important historical events relevant to ancient Christianity. These include Herod’s death date, Christ’s birth date, John the Baptist’s ministry, Christ’s Crucifixion date, and Paul’s conversion date and death date.

Remarkably, these dates can be determined with some reliability and interrelate with each other in a smooth historical narrative. Of course, the dates are certainly still a manner of considerable controversy and some speculation, and certainly, there is no consensus of agreement among historians as to their correctness. But the fact that such a narrative can be given as a hypothesis lends some credence to their reliability.

Paul’s Scriptural timeline is difficult to put together in a cohesive manner resulting in considerable controversy about the specific dates of his ministry. However, this is a doable enterprise because there are interlock dates with historical figures throughout his life, making dating somewhat less ambiguous. In his book A Chronology of Paul’s Life, Robert Jewett attempts to trace the lifespan of Paul against these historical figures whose dates are known. This interlocks Paul’s history with these historical figures and provided a baseline upon which the rest of his life history can be laid out in a cohesive manner.

Broad Outline of Paul’s Life and Conversion Date

His book attempts to produce the most reliable historical outline possible within the reasonable limits of what we know. The first problem was determining what portion of Scripture provides the most accurate portrayal of these dates. Jewitt believes the historical evidence derived from the Pauline letters to be more accurate than the secondary evidence in the Book of Acts. This is because more historical details allowing us to map out his life. Using this technique, a broad outline of Paul’s life from conversion to death is as below:

- Conversion (Gal. 1:15-16; 1 Cor 15:8)

- Three Yeat Time-Span (Gal. 1:18)

- First Jerusalem Visit (Gal. 1:18-19)

- Missionary Activity (Gal 1:21)

- Fourteen Year Time-Span (Gal. 2:1)

- Second Jerusalem Visit (Gal. 2:1-10)

- Missionary Work, Including Collegiong (1 Cor. 16:1-8)

- Third Jerusalem Visit (Romans 15:25-33)

- Imprisonment and Execution

Early Life Before Paul’s Conversion Date

There is little known about Paul’s early life besides what can be gleaned from Scripture. He likely was born sometime between 5 BC and 5 AD and was a Roman citizen by birth. He was from a devout Jewish family from the tribe of Benjamin and was raised in the city of Tarsus.

Paul describes himself as being “a Hebrew of the Hebrews, as touching the law, a Pharisee.” (Phil 3:5). Paul’s sister’s son is mentioned in Acts 23:16, and in Romans 16:7, he states that his relatives Andronicus and Junia were Christians before his conversion and were prominent among the apostles.

Paul was an artisan involved with leather crafting and tent-making. This would be his initial connection to Priscilla and Aquila, with whom he would partner in the business. Paul seemed to take some pride that he could support himself with his business and did not need support from others.

Gallio and the First Historical Interlock

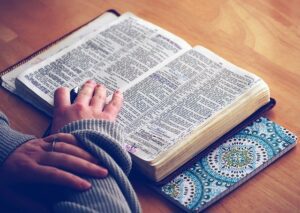

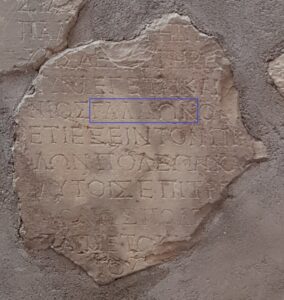

Gallio’s name written in Greek on a stone – By Gérard – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

An interlock occurs when Paul’s life interacts with a historical figure whose relevant dates are known. Gallio is the first historical figure in this narrative.

Gallio is mentioned in Acts 18:12-17:

While Gallio was proconsul of Achaia, the Jews of Corinth made a united attack on Paul and brought him to the place of judgment. “This man,” they charged, “is persuading the people to worship God in ways contrary to the law.”

Just as Paul was about to speak, Gallio said to them, “If you Jews were making a complaint about some misdemeanor or serious crime, it would be reasonable for me to listen to you. But since it involves questions about words and names and your own law—settle the matter yourselves. I will not be a judge of such things.” So he drove them off. Then the crowd there turned on Sosthenes the synagogue leader and beat him in front of the proconsul; Gallio showed no concern whatever.

Gallio was a man of considerable importance primarily due to his family. He was the son of Seneca the Elder and the elder brother of Seneca the Younger, who was born in Cordoba in what is now Spain in 5 BC. He was adopted by Lucius Junius Gallio, from whom he took his name, Gallio.

Gallio and his brother Seneca were likely banished to the island of Corsica but achieved some restitution when Seneca was selected to tutor Nero. Galio then became proconsul of the province of Archeae but had to resign, likely due to poor health. Achaea is situated in Greece (in the Peloponnese peninsula), not far from Corinth.

When Gallio was proconsul in Achaea, Paul was brought before him by leaders from the local synagogue. He was accused of leading the local Jews toward Christianity – which was “contrary to the law.” Gallio could not care less about local Jewish customs and had them all thrown out of court.

Emperor Claudius – By Anonymous – Photograph: Luis García (Zaqarbal), 14 May 2006., Public Domain, Link

The important facet of this story is that it fixes Paul’s visit during Gallio’s proconsulship, between July 1, 51 through July 1, 52 AD. So then we know the time of Paul’s visit in Corinth just next door to Achaea to be eighteen months (Acts 18:1) which would place his time there from about January 1, 50 AD to July 1, 51 AD.

Emperor Claudius and Expulsion of Jews from Rome

The Roman Emperors never knew quite what to do with Christians living in their midst. Their knee-jerk reaction seems to have been persecution – they did not accept Roman ways and insisted on their peculiar customs and beliefs.

But when Christians refused to worship the Roman gods – that was just too much. They even refused to worship the Roman Emperor which was just beyond the pale. Moreover, most of the Christians in Rome were Jewish, so Claudius just had them all expelled from Rome in 49 AD.

This is important in our dating narrative because of the arrival of Priscilla and Aquila from Rome at the beginning of Paul’s Corinthian ministry. This helps establish our timeline since they were expelled in 49 AD, and Paul probably started his Corinth ministry in 50 AD, having his trial before Ballio in about 52 AD.

Paul’s conversion date and other important mission dates seem to come together.

The Framework of Time Spans

While all of this is interesting in its own right, it also helps us determine the likely year of Paul’s conversion. This is important because knowing this year helps to determine when Christ was crucified. Thus, the dates of the Crucifixion and Paul’s conversion are likely close together and not separated by multiple years.

Jewitt puts together an experimental hypothesis to make this determination. The hypothesis assumes three Jerusalem journeys interspersed with multiple missionary trips and other historical events (like the trial before Gallio). This framework is put together primarily through hints provided by Paul’s various letters and less detailed history in the Book of Acts.

The framework is outlined below,

- Conversion – August-October 34

- Escape from Aretas – 34

- Three-Year Timespan in Arabia – 34 – 37

- Return to Damascus – 37

- First Jerusalem Visit – 37

- Death of Herod Agrippa I = 44

- Fourteen Year Time Span 37 – 51

- Paul’s Arrival in Corinth – 50

- Departure from Corinth 18 months later – 51

- Apostolic Conference in Jerusalem – 51

Damascus and Aretas

The little-known Roman ruler over Damascus, Aretas, plays a large role in determining these dates. If it were not for his mention in Scripture and having an important part to play in the early life of Paul, he would likely have been lost to obscurity.

He was a Nabataean ruler of the country east of the Jordan River and particularly of the beautiful city of Petra. He was also the father of Phasaelis, who was married to Herod Antipas.

Herod’s eyes were wandering, and he decided to divorce Phasaelis to marry his brother’s wife, Herodias. Fearing for her life, Phasaelis fled to her father when she heard about Herod’s plans to divorce her (possibly resulting in her untimely demise), and the rest is history.

Scripture tells us that John the Baptist was a prisoner of Herod Antipas and scolded Herod for marrying his brother’s wife. Herod was annoyed but afraid to do anything to John because he was so popular with the people.

The sordid story is portrayed in Scripture,

At that time Herod the tetrarch [Herod Antipas] heard the reports about Jesus, and he said to his attendants, “This is John the Baptist; he has risen from the dead! That is why miraculous powers are at work in him.”

Now Herod had arrested John and bound him and put him in prison because of Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife, for John had been saying to him: “It is not lawful for you to have her.” Herod wanted to kill John, but he was afraid of the people because they considered John a prophet.

On Herod’s birthday, the daughter of Herodias danced for the guests and pleased Herod so much that he promised with an oath to give her whatever she asked. Prompted by her mother, she said, “Give me here on a platter the head of John the Baptist.” The king was distressed, but because of his oaths and his dinner guests, he ordered that her request be granted and had John beheaded in the prison. His head was brought in on a platter and given to the girl, who carried it to her mother. John’s disciples came and took his body and buried it. Then they went and told Jesus.

Aretas was unhappy that Herod had divorced his daughter, and he invaded Herod’s domain defeating his army. However, Antipas managed to escape capture with the help of Roman forces. Antipas then ran to Rome to complain to Emperor Tiberias, who dispatched Lucius Vitellius to attack Aretas. Vitellius arrives with his soldiers only to hear that the Emperor had died and then abandons his mission.

We know that Tiberias died in 37 AD, and Aretas himself died in 40 AD placing upper limits on Paul’s conversion dates.

Herod Agrippa I and Herod Agrippa II

Herod Agrippa I

The Herodian Dynasty is complex and often confusing. One of the more difficult aspects of this dynasty concerns two very different Herodian leaders, both in Scripture and important for our discussion.

Herod Agrippa I is the Herod mentions in Acts 12:1, and was King of Judea from 41 – 44. Agrippa tried to gain favor from the Jews by understanding their sensitivities and religious observances. For example, coins minted during his reign did not have a Roman deity or human figure in deference to Scripture commands not to make any graven images.

He also interceded with the Roman Emperor Caligula to convince the empower not to set up his status in the Temple at Jerusalem. He convinced Caligula not to desecrate the Temple with his status, which certainly would have led to serious unrest and likely riots from the Jewish community.

He further tried to ingratiate himself with the Jews by persecuting the rival Christian church in Jerusalem. He had James, the son of Zebedee, killed and imprisoned Peter about the time of the Passover.

Agrippa did not live long after his Christian persecution. He developed heart and abdominal pains and died in a few days. Acts 12 indicates that an angel struck him down, eaten by worms, and died.

Herod Agrippa II

Herod Agrippa II was seventeen years old when his father died. The Empower Claudius eventually made him a tetrarch of the Syrian kingdom, Calcis, and the responsibility to supervise the Jerusalem Temple. He eventually gave up Calcis but was granted the title of “king” and given more territory, including some of Galilee.

Herod Agrippa Lived with Bernice, a daughter of Herod Agrippa I (or Agrippa II’s sister). She was originally married to Herod Antipas, but after he died, she moved in with her brother, Agrippa II, in an incestuous relationship.

Agrippa II’s claim to fame is his appearance in the New Testament in Acts 25 and 26. Paul was arrested by the Jews in Jerusalem for the trumped-up charge of Temple desecration. A centurion had him under heavy guard to prevent his assassination and brought him to the Roman governor Felix in Caesarea (Acts 23). Felix hoped Paul would offer him some form of bribe to be set free, but after two years, Felix was succeeded by Porcius Festus. Paul remained imprisoned because these feckless Roman rulers did not want to anger the Jews.

Festus asked Paul if he would consider standing trial in Jerusalem. Paul wisely countered he could not get a fair trial there and invoked his right as a Roman citizen to appeal to Caesar: “I am now standing before Caesar’s court, where I ought to be tried. I have not done any wrong to the Jews, as you yourself know very well. I do not refuse to die if I am guilty of doing anything deserving of death. But if the charges brought against me by these Jews are not true, no one has the right to hand me over to them. I appeal to Caesar!” (Acts 25:10-11).

Festus had no choice but to send Paul to Rome to plead his case before Caesar. But then, the story takes an interesting turn. Festus could not understand what charges could be made against Paul because he had not broken any Roman law. Festus then discussed Paul’s case with Agrippa II and wanted to hear from Paul himself.

The next day, Agrippa II, Festus, and Bernice gathered to hear Paul and gather information about him to forward to Rome for his trial before Caesar. Paul was then brought before them and began his defense. Paul said,

King Agrippa, I consider myself fortunate to stand before you today as I make my defense against all the accusations of the Jews, and especially so because you are well acquainted with all the Jewish customs and controversies. Therefore, I beg you to listen to me patiently. (Acts 26:1-3)

Festus was not buying Paul’s arguments, saying,

You are out of your mind, Paul! … Your great learning is driving you insane.” (Acts 26:24).

Paul then replied to Festus,

I am not insane; most excellent Festus … What I am saying is true and reasonable. The kind is familiar with these things, and I can speak freely to him. I am convinced that no one of this has escaped his notice because it was done in a corner. King Agrippa, do you believe the prophets? I know you do! (Acts 26:25-27).

Then, King Agrippa uttered these words, which have been debated over the past 2000 years,

Do you think you can persuade me to be a Christian in such a short time? (26:28).

His claim to fame would be that he might have become a believer. This interaction likely occurred in 59 or 60 AD.

Piecing it Together

Paul was converted “on the road to Damascus” is a story very familiar to every Christian (Acts 9). In this story, Christ appears to Paul in a blinding light, demanding to know why Paul was persecuting him. Paul realizes his terrible mistake in persecuting the Christians, and his life takes a complete change.

He continues to Damascus, where he originally would arrest Christians but now has come to become a Christian. Paul stays with some Christians in Damascus and starts proclaiming Jesus in the synagogues, saying, “He is the Son of God.”

But Paul had a problem; the Jews hated him for preaching and decided he must go. The Jews’ desire to kill him became known to Paul, who needed to get out of the city before accomplishing their goals. (2 Cor. 11:32)

His Christian colleagues took him to the city gates under cover of night and lowered him in a basket through a window.

The Three-Year Time Interval

Paul escapes from the Jews in Damascus who wanted him dead for subverting the Scriptures and preaching blasphemy. There is no doubt that Christ’s message was considered blasphemous by religious Jews and that they should stone anybody preaching it.

Paul left Damascus with his life and went to the countryside to learn more. I will let him describe what happened in his own words,

I want you to know, brothers and sisters, that the gospel I preached is not of human origin. I did not receive it from any man, nor was I taught it; rather, I received it by revelation from Jesus Christ. For you have heard of my previous way of life in Judaism, how intensely I persecuted the church of God and tried to destroy it. I was advancing in Judaism beyond many of my own age among my people and was extremely zealous for the traditions of my fathers. But when God, who set me apart from my mother’s womb and called me by his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son in me so that I might preach him among the Gentiles, my immediate response was not to consult any human being. I did not go up to Jerusalem to see those who were apostles before I was, but I went into Arabia. Later I returned to Damascus. Then after three years, I went up to Jerusalem to get acquainted with Cephas and stayed with him for fifteen days. I saw none of the other apostles—only James, the Lord’s brother. I assure you before God that what I am writing you is no lie. (Galatians 1:11-20)

Most scholars today believe that Paul did not travel all the way to what is now known as Arabia – hundreds of miles away. Rather, the geographical area of Arabia refers to the area surrounding Damascus. It would seem that Paul spent three years receiving instructions (revelations) from Christ as to the Christian gospel that he would later preach and write about in his epistles. (Gal. 1:17).

Then Paul describes how he went back to Damascus (Gal. 1:17) and went to Jerusalem to “get acquainted” with Peter, with whom he stayed fifteen days. Paul then spends fourteen years on a missionary trip (Gal 2:1), which would have him going to Jerusalem in about 51 AD.

Summary of Paul’s Conversion Date

The timespan backward from the known date in history (Gallio’s rule in Achaea) allows us to place the conversion of Paul in 34 AD reasonably.

This would be just after the most likely Crucifixion date of Christ in 33 AD making the whole historical narrative come together. To be sure, there are other ways we could put the narrative together, but no other narrative makes this much sense following known historical dates.

We can now make a smooth timeframe enveloping the life of Christ, John the Baptist, and now Paul, from Herod the Great’s death date to Paul’s conversion date.

Herod’s death date is confirmed by pairing with Josephus’s ancient history and one particularly noticeable lunar eclipse. Christ’s birth date is paired with Herod’s death date, as we know Christ was born before Herod’s death. Finally, John the Baptist’s birth date is paired with Christ’s birth date, and John’s beheading is paired with Christ’s Crucifixion.

This flow of history substantiated by verifiable historical events demonstrates the historicity of the Scriptures and helps us better understand the times in which these events occurred.