Christianity and Education

Christianity and education have been closely allied since the very beginning. Christians understand that the world is knowable, that there is math behind much of the complicated machinery of the universe. Furthermore, Christians believe we are meant to discover and explore our environment and figure out how to make the world a better place.

Because of the recognition that the world is knowable, Christians have been at the forefront of science and education since its founding. The modern school system with mandatory attendance, graded structure, and university system are all innovations that changed the world. These innovations are largely responsible from Christians and their worldview.

The Bible paints a world that is knowable, and that we are supposed to explore and understand this world.

Even those who are opposed to Christianity admit Christ was a great teacher. He taught with stories, parables, and circumstances that attempted to teach some truth to the common man. One historian noted,

Had Christ left this world without making any provision for carrying on His work, He would still have been the greatest teacher of all time, and His life and example would have influenced profoundly the whole development of educational theory.

The early followers of Christ recognized the central need for education. For example, Paul in his epistles makes note of Christians teaching throughout the then known world in Ephesus, Corinth, Rome, Thessalonica, and other places.

The first Christians were Jews and the Jewish tradition considered education in the principles of Judaism to be very important. But arguably the early Christians had an even stronger imperative to promote education. It was a matter of heeding the Great Commission that Christ had given to the apostles and all future Christians (Matthew 28:19-20).

The Didache (Greek for “Teaching”) was an instruction manual for new converts to Christianity that appeared during the latter portion of the first century. The first line of the Didache (also known as The Lord’s Teaching Through the Twelve Apostles to the Nations) is

The teaching of the Lord to the Gentiles (or Nations) by the twelve apostles.

It represents the oldest written catechism with three main sections dealing with Christian ethics, ritual (such as baptism and Eucharist), and Church organization. Ignatius, a bishop of Antioch and one of the early Church Fathers, urged children to be taught the Holy Scriptures and learn a skilled trade.

Catechism

Teaching the basics of Christianity to early converts was a priority. Early newcomers to the church were instructed as “catechumens” by an oral question and answer method. This was in preparation for baptism and church membership. The instruction would last for several years and be given to both men and women.

At first, catechumens were instructed in the teacher’s home, but formal schools were established when this became difficult or impractical. Justin Martyr, one of the greatest early church scholars, established such catechetical schools in various cities including Rome and Ephesus. Clement established a prominent school in Alexandria, Egypt which was considered one of the best schools in existence at the time.

Catechetical schools provided the initial education of some of the greatest early Church theologians including Origin (185-254) and Athanasius (296-373). Some of these schools also taught other subjects in addition to early Christian education including mathematics and medicine.

These catechetical schools were established as centers of excellence and acquired a favorable reputation throughout the Roman world. Historian William Boyd noted that

Christianity became for the first time a definite factor in the culture of the world.

Education of Both Sexes

Early Christians appear to have been the first group to teach both sexes in the same setting. From its inception, Christianity did not place a difference in the importance of men and women. Both men and women received catechetical education before becoming full-fledged members of the Church. Additionally, formal education is often continued after baptism to ensure understanding of important church doctrine.

Before the time of Christ, most Roman schools did not formally educate women at all – let alone educate them together with boys. Also, the ones citizens to receive education at all came from the ruling class. This education was often done in their gymnasia where girls were excluded.

The teaching of both sexes together from all classes of people was a Christian invention. W.M. Ramsay notes that the aim of early Christianity was

universal education, not education confined to the rich, as among the Greeks and Romans … and it [made] no distinction of sex.

This emphasis on education produced results. St. Augustine noted that Christian schools were producing educated students of both sexes. He noted that Christian women were often better informed than the pagan male philosophers.

Episcopal Schools

Christians also educated their children (both boys and girls) at the local cathedral beginning about the fourth century. Before this time, it was very difficult to have formal education in a public place due to intense intermittent persecution.

These schools maintained not only Christian education but also a diverse, liberal education experience. The episcopal schools commonly taught the liberal arts including the trivium (rhetoric, grammar, and logic) and the quadrivium (including arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy). The children were usually taught by the bishops associated with the cathedral and by priests and others.

The concept of formal Christian education proved to be very popular and spread to the local parishes. The local church often provided a parish or parochial school that would instruct children in church history and doctrine.

Since women joined the early church in greater numbers than men, catechetical and episcopal schools usually instructed more women. However, boys outnumbered girls in the episcopal or cathedral schools. Girls received their education mostly in the arts in convents or nunneries.

Universal Education

The historian Will Durant described Christianity as being inclusive to all peoples,

without reservation to all individuals, classes, and nations; it was not limited to one people, like Judaism, nor to the freedmen of one state, like the official cults of Greece and Rome.

The sixteenth century brought about universal education during the time of the Protestant Reformation. The early church catechized individuals equally from all social classes and ethnic backgrounds. But this practice had significantly deteriorated by the time of Luther. He visited the churches in Saxony only to find widespread ignorance and congregant with little if any formal education.

He wrote the short Catechism in 1529 to help address this ignorance of the faith. He notes finding common people with little or no knowledge of the Christian teachings in the preface to this catechism. What was perhaps even worse was that many of the pastors were not competent to preach. Luther faulted the bishops and wondered how they would someday answer for the state of their churches.

Luther urged a state school system “to include vernacular primary schools for both sexes. Latin secondary schools, and universities. He felt that parents who did not see to the proper education of their children were “shameful and despicable.”

William Boyd noted that,

Luther, in fact, wanted a system of education as free and unrestricted as the Gospel he preached [and] indifferent, like the Gospel, to the distinction of sex or of social class. (The History of Western Education, William Boyd, 1965)

John Calvin was another leader of the Protestant Reformation who also advocated universal education for children. His Geneva plan called for

a system of elementary education in the vernacular for all, including reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar, and religion, and the establishment of secondary schools for the purpose of training citizens for civil and ecclesiastical leadership.

The universal education plans of both Luther and Calvin were not modeled after a secular counterpart but were rather a logical consequence of the Church’s desire that every person is responsible for their own salvation according to Lars Qualben.

Tax Supported Public Schools

Tax-supported public schools are a common experience throughout the modern world; however, this was not always the case. They seem to have originated with Martin Luther. Before Luther, most education was supported and operated through the church in the episcopal and cathedral schools.

Because of the ignorance Luther noted among the common people, he came to lose confidence in the ability of the bishops to see to the education of the people. Many of these people were illiterate, and most children stayed home and received no formal education. Most parents not only did not educate their children, but they also had no ability or interest to do so.

Luther felt that such ignorance and illiteracy could spell doom for the church and modern society in general, and felt it important to rely on civil society for their children’s education.

Philipp Melanchthon (1497 – 1560) worked with Luther and is often called “the preceptor of Germany.” He helped Luther to persuade civil authorities to implement the first public school system in Germany. The organization of these schools was an accomplishment of Johannes Bugenhagen, pastor of St. Mary’s church in Wittenberg, where Luther attended and preached.

Bugenhagen first encountered Luther when he read Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church in 1520. He initially did not approve of Luther’s interpretation of Scripture as promulgated in Prelude but became a supporter of the Reformation and moved to Wittenberg.

He became a part of Luther’s team translating the Scripture from Greek and Hebrew to German and became one of the most influential teachers of biblical interpretation in the Protestant Reformation. He also is known as the father of the German public school system for his efforts for spreading childhood education throughout Germany.

Jan Comenius – By Jürgen Ovens – http://www.rijksmuseum.nl/collectie/SK-A-2161, Public Domain, Link

John Comenius (1592 – 1670) brought Luther’s idea of universal education to children of all ages, especially the poor. He recognized the wealthy had meant to educate their children. He established a school in Fulneck where he taught children of all social classes. Alvin Schmidt notes,

the desire to have public tax-supported schools, whether wise or not, even in a society where Christian values predominate, has its roots in the thinking of prominent Christian reformers like Luther and Comenius. Although public schools have by now become totally secularized, especially in the United States, it is helpful to know that the idea of tax-supported schools originated with individuals who were motivated by the love of Jesus Christ, whom they wanted taught for people’s spiritual and material benefit.

Comenius introduced many reforms to the educational system of his day. He developed pictorial textbooks in the native language of the students rather than in Latin (which few of them understood), teaching based on gradual development from simple to more complex, logic over rote memorization, education for women, and universal instruction.

His influence extended to the nineteenth century with his outline of a system of schools reflected in the American system of kindergarten, elementary school, secondary school, college, and university.

Compulsory Education

For most of the world’s history, children were important only as they might help the family business. This business often was farming and children – especially boys- served on the family farm as soon as they were able.

Formal education past that which was needed to run a farm was considered a luxury, and most families could not afford any luxuries. Most children grew up illiterate with little or no formal education, could not read the Bible, and were totally dependent upon clergy for knowledge concerning their faith.

Luther is generally considered to have “enunciated the most progressive ideas on the education of the German Protestant reformers.” Luther was so sure of the value of public education that he would tell civil authorities they should compel children to attend school. Luther noted,

I hold that it is the duty of the temporal authority to compel its subjects to keep their children in school, especially the promising ones we mentioned above.

Good and Teller noted that Luther was

the first modern writer to urge compulsory [school] attendance and proposed that the state should pass such legislation and enforce it.

Luther found resistance from the German populace and civic leaders toward compulsory education. Many Germans had a great distrust of clergy stemming from the papal corruption of the Catholic Church. Working men also harbored a feeling that educated people had it too easy in life. However, Luther felt that the lack of education would bring ruination to the church and society in general. An uneducated, illiterate society can hardly be expected to govern itself.

Luther had to settle for what he could get. He tried to convince civic leaders that all children should be compelled to go to school – at least one hour a day for girls and two hours a day for boys.

Luther’s conviction gradually changed the mind of the German people and children were encouraged to attend some form of civic education. The appeal had its effect and roused many of the councilmen to action. Up to 1600, at least 300 city and town schools were established in German lands. In 1537 a Roman Catholic theologian, John Zwick, confessed that if he were a boy again he would attend Lutheran institutions rather than those of his own church, on account of the greater thoroughness of the former.

La Salle – By Unknown author – Unknown source, Public Domain, Link

Other areas of Europe were slower in the adaptation of compulsory education of children. LaSalle, a Roman Catholic priest advocated compulsory education in France one hundred years later.

Graded Education

Graded education was introduced by Johannes Sturm (1507-1589) a Lutheran layman. He believed that having progressive grades would motivate students to stay in school to get promoted to the next level. Sturm ideal in education was

to direct the aspiration of the scholars toward God, to develop their intelligence, and to render them useful citizens by teaching them the skill to communicate their thoughts and sentiments with persuasive effect

Sturn was a religious man who believed students should be taught about Christian values, as without these values all other educational efforts were wasted. Today, students throughout the world are taught at different levels, elementary, secondary, and higher education. While many people value this system and value the compulsory education of children, few recognize that behind this graded system are men who advocated education to learn more about their Savior.

Kindergarten

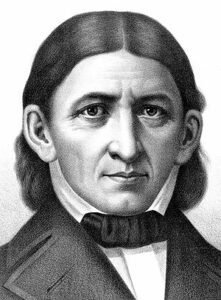

Froebel – By C.W. Bardeen, publisher – Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-PGA-00127 (digital file from original print), uncompressed archival TIFF version (168 MiB), level color (pick white and black point), cropped and converted to JPEG (quality level 88) with the GIMP 2.4.5., Public Domain, Link

Kindergarten is not a recent invention but has its roots in the 19th century. It was popularized by Friedrich Froehel (1783 – 1852) who originated the concept of the kindergarten school.

Froebel was a devout Christian who was the son of a Lutheran pastor. He was convinced that children needed to be instructed beginning at an earlier age than the first grade. Interestingly, the name “kindergarten” comes from Frobel’s experience as a child. During his youth, he would work with his father in the family garden. One day while walking in the mountains, he came up with the idea that children should begin their education from an expert “gardener” (teacher) in a children’s garden – hence the name derived from German – Kindergarten.

Froebel recognized children had unique needs and capabilities that were different from older children. He developed the concept of educational play materials for young children called “Froebel gifts.” The play was encouraged with these toys such as singing, dancing, and growing plants. Froebel noted,

The active and creative, living and life-producing being of each person, reveals itself in the creative instinct of the child. All human education is bound up in the quiet and conscientious nurture of this instinct of activity; and in the ability of the child, true to this instinct, to be active.

The great insight of Froebel was to recognize the need for children to integrate self-directed play with learning.

The first kindergarten in the United States was taught in German by Mrs. Carl Schurz in Watertown, Wisconsin in 1855. Her husband later served under President Abraham Lincoln as a Union general in the Civil war, and later as the Secretary of the Interior. The first English-speaking kindergarten began in Boston in 1860 and was founded by Elizabeth Peabody. Just like Froebel, Peabody embraced the idea that children’s play has intrinsic developmental and educational value.

Today, virtually all industrialized first-world countries enable their young children to attend Kindergarten schools. The influence of Frobel’s Christian belief that children needed to be instructed at a very early age greatly changed the world in the field of early childhood education.

Education for the Deaf

Before the onset of organized education for the deaf, deaf people were considered “idiots” who were incapable of education. After the foundation of schools for the deaf, this attitude changed and the world of education opened to deaf students.

The strong Christian convictions of three individuals were instrumental in the foundation of schools specifically for teaching the deaf. These people were Abbe Charles Michel de l’Epee, Thomas Gallaudet, and Laurent Clerc.

L’Epee was born into a rich family in Versailles, France, and became a Catholic priest due to his religious convictions. He had a chance encounter with two young deaf sisters who communicated with sign language. L’Epee then decided to dedicate himself to education and ultimately to the salvation of deaf people who otherwise would never hear the Gospel. He founded a school in 1760 which became the world’s first free school for the deaf open to the public.

In this school, he developed the “instructional method of signs.” This method emphasized using gestures or hand signs, based on the principle that

the education of deaf-mutes must teach them through the eye of what other people acquire through the ear.

He developed a gestural system representing all the verb endings, articles, prepositions, and auxiliary verbs of the French language.

His methods became influential largely because his schools were open to the public. He also established teacher-training programs for those speaking other languages who could then take the method to their country and establish schools for the deaf around the world.

Laurent Clerc was a deaf pupil of the Paris school who then founded a school for the deaf in North America. He was also a devoted Christian and wrote that L’Epee and Gallaudet were both concerned about “saving the pupils’ souls.” Clerc is known as “The Apostle of the Deaf in America” and is often regarded as the most renowned deaf person in America. He co-founded (along with Thomas Hopkins and Fallaudet” the first school for the deaf in North America, the Asylum for the Education and Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb in 1817. The school was later renamed the American School for the Deaf and remains the oldest existing school for the deaf in North America.

Thomas Gallaudet founded what became known as Gallaudet University.

Gallaudet would improve on the sign language taught to French students by L’Epee. The Gallaudet sign language could be read, written, and communicated. In addition to co-founding the American School for the Deaf, he also founded a school for the deaf in Washington, D.C. known now as Gallaudet University. The University is the only higher education institution in which all programs and services are specifically designed to accommodate deaf and hard-of-hearing students.

Gallaudet University is also officially bilingual with American Sign Language and written English being the two languages used there. All classes are conducted in American Sign Language with all student desks being arranged in a circle to see each other to enable discussion.

History demonstrates how deaf education originally arose as the product of Christian motivation. Epee, Gallaudet, and Clerc were all dedicated, devout Christians who played key roles to establish the modern system of deaf education.

Education for the Blind

Being blind in the Greco-Roman world led to a usually short, brutal existence. Infants who were born blind were usually tossed into the river or abandoned in the wilderness to die.

Boys who became blind were destined to become slaves, while girls would frequently be destined for a life of prostitution. Little is known about how the early Christians cared for the blind until the fourth century. Several asylums operated by Christians were built and in 630 a typholocomium (typholos = blind, komeo = take care of) was built in Jerusalem.

Louis IX (after St. Louis is named) built the famous Hospice des Quinze-Vingts hospital for the blind founded in 1260. The name “Quinze-Vingts” is French for fifteen twenties or 300, which represents the product of 15 and 20. Math in the middle ages was based on base 20 (vigesimal) rather than on base ten (decimal) that we use today. The name of the hospice was based upon the number of beds in the hospital reserved for poor, blind Parisians (300).

Attempts were made to teach blind persons to read using raised letters on wood. This was not a very practical means for conveying information and certainly not for reading a book.

The greatest leap in education for the blind would have to wait until the 19th century with the instructional methods developed by a devout Christian, Louis Braille. Braille lost his sight when his eye was accidentally stabbed with an awl in his father’s harness shop in Couypvray, France. Apparently, the injury was so severe that it infected the other eye as well and he became totally blind. Louis attended mass every Sunday and became a church organist when he was a teenager. He attended the first school for the blind founded by Valentin Hauy starting in 1819.

Interestingly, Hauy decided to help the blind after an experience in 1771 when stopped for lunch at a cafe on the Place de la Concorde in Paris. While eating lunch, he witnessed several people from the Quinze-Vingts hospital for the blind being mocked for their blindness. The mockers made the blind patients wear dunce caps and oversized cardboard glasses and told them to play their instruments at a religious street festival. He decided at that time to found a school with Charles-Michel de l’Epee that we met earlier.

Barbier’s system was related to the Polybius square, in which a two-digit code represents a letter. In Barbier’s variant, a 6×6 square box includes most of the letters of the French alphabet, as well as several digraphs and trigraphs:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | i | o | u | é | è |

| 2 | an | in | on | un | eu | ou |

| 3 | b | d | g | j | v | z |

| 4 | p | t | q | ch | f | s |

| 5 | l | m | n | r | gn | ll |

| 6 | oi | oin | ian | ien | ion | ieu |

A letter (or digraph or trigraph) was represented by two columns of dots, in which the first column had one to six dots denoting the row in the square and the second had one to six dots denoting the column: e. g. 4-2 for “t”. The system was not very user-friendly as some symbols would require two columns each with six dots.

He eventually presented his concept to the French Royal Academy of Sciences, and later to students at the Royal Institution for Blind Youth in Paris. The blind students were favorably impressed with his system as the older system of embossed letters was much harder to interpret for the blind.

Louis Braille just happened to be at the institution at that time and was introduced to Barbier’s method. Brail reduced the number of dot positions from six in two columns to six in two columns which were easier to scan with fingers. The six-dot system was recognized by the French government in 1844, and the Braille system is still widely used today.

When Braille was dying, he said,

I am convinced that my mission is finished on earth; I tasted yesterday the supreme delight: God condescended to brighten my eyes with the splendor of eternal hope.

The Braille system revolutionized education for the blind and was produced by a deeply religious person endeavoring to better the lives of those blind like him.

Summary of Christianity and Education

Over the past two millennia, Christianity has been at the forefront of advancing education for the average person. This included the promotion of Kindergarten for very young children along with primary, secondary, and university education for older children.

Central to this promotion of education was the understanding that reading Scriptures was central to their development as an informed Christian. Rather than just believing in a priest or pastor’s interpretation of Scripture, the average person could develop their own opinion.

Education would be offered to both sexes, allowing girls as well as boys to attend the same schools and be involved in the same curriculum. The great Reformation leader Martin Luther was able to improve education throughout Germany, and eventually develop compulsory education. He recognized the worsening ignorance of the population and the inability to read even the simplest texts. This growing ignorance was self-perpetuating as the populace increasingly ignored education as something important.

Christians were also influential in extending education to the less fortunate in society; impoverished people, and those who were blind or deaf. This enabled disabled students to work their way into the larger society and improved their lives greatly.

Christianity has always been interested in promoting education, as through education the average person could become a better informed Christian. Having a better life means less crime, longer lives, and increasing wealth and prosperity.

Charter schools and homeschooling represent two new areas receiving increasing attention from Christians wishing to escape state indoctrination in government schools. This will be an important area for future development in the relationship between Christianity and education.

Hello there

Thank you for this great post about christianity and education. Christianity and education have been closely allied since the very beginning. Christians understand that the world is knowable, that there is math behind much of the complicated machinery of the universe. I think this is very right. Totally agree. Its good to know that most of the innovations have been sparked off by christian world view.. How powerful!

Thank you very much, Paul, for your insightful comments on my post. I totally agree that the emphasis on “reason” promulgated by early Christianity led them to investigate the actual causes behind effects rather than just use philosophy as was so popular before them (as with Aristotle).

Thanks again for your kind comments.

Dave.

Thanks for providing people with this interesting article. It’s always great to learn about the different religions and their history.

I just learnt that Christians were one of the first to teach both genders but before that it was mainly aimed at males. Keep writing these informative posts! It’s important to get to know other religions of the world as well as your own!

Thank you for your kind remarks. I am trying to write good material that would not be an offense to other religions and try to be as truthful as possible.

Dave.