Bad Design Features

Bad Design Features

Bad Design Features

Evolutionary scientists have had a field day with what are supposed to be “bad design features” of the human body. These scientists bring up several design features which seem to work against the purpose of the organ system involved.

The late Stephen Gould presented examples of what he considered “bad design” as an argument against a creator. The best-known example was that of the panda’s thumb which he described as being clumsy.

Another classical example of allegedly poor design is the human retina which seems to be inverted with the light-sensing cells behind a membrane. This means that light transfer is inhibited by forcing the light to travel through neuronal cells first before landing on the light-sensitive cells of the retina.

Animals need to cool themselves in hot weather or when producing body heat during exertion. Enzyme systems within the body are very heat sensitive and do not work well at higher temperatures. Unlike humans, most animals do not have many sweat glands to cool themselves and so are at a disadvantage when stressed by increasing body heat.

But are these criticisms valid and has further research provided answers as to why the supposedly “bad” arrangement occurs? We shall investigate these arguments in this section. Matan Shelomi worries about how “awful” the human body is. He (along with other evolutionary biologists) argues the human body is badly designed and this shows how we are the product of a blind evolutionary process. He complains,

To say that humans were ‘intelligently designed’ by a ‘creator’ is to insult God because our bodies show no intelligent design at all.

Shelomi seems extreme to argue the human body shows no design feature “at all” by ignoring countless marvels of the human body that far outstrip anything that modern science can produce in any of its advanced laboratories. Instead, he chooses to focus on a few alleged problems.

The Panda’s Thumb as a Bad Design Feature

The crux of Gould’s argument concerning the “thumb” of a panda is that it is not optimally designed for its purpose. Apparently, the panda uses its thumb to strip the bark off of bamboo shoots, and in this respect, the thumb is poorly designed compared to the opposable thumb of humans and is therefore thought to be of poor design.

But it actually turns out that the panda’s thumb is not poorly designed at all! Further research has demonstrated the panda’s thumb is properly designed for what its purpose. The panda’s paw and “thumb” are not meant for fine manipulation like out opposable thumb, but rather is meant for a very different task – to strip the leaves and back off bamboo – the primary meal for pandas.

Japanese biologists have subsequently examined the panda’s thumb more thoroughly to determine whether it is poorly designed for its major purpose in helping it get food. They found that using three-dimensional computerized tomography and MRI evaluation that certain bones of the panda’s hand for a double pincer-like apparatus which actually allows it to “manipulate objects with great dexterity.”

The researchers go on to praise the functionality of the panda’s thumb noting,

[t]he way in which the giant panda … uses the radial sesamoid bone — its ‘pseudo-thumb’ — for grasping makes it one of the most extraordinary manipulation systems in mammalian evolution.

An opposable thumb would not be a good design to allow twelve hours per day of stripping bark and leaves from bamboo shoots while the panda’s thumb does very well in this task.

The Human Eye Retina as a Bad Design Feature

Evolutionists have argued the retina is poorly designed because the light-sensitive cells are located in the back of the eye rather than in the front where they might be better able to sense light.

Furthermore, nerve cells that transmit light signals to the brain are between the light-sensing cells and the incoming light. This design would seem to disrupt the ability of the eye to see.

The evolutionist Richard Dawkins published the book titled The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design. Dawkins argues the eye is poorly designed for its purpose,

Any engineer would naturally assume that the photocells would point towards the light, with their wires leading backwards towards the brain. He would laugh at any suggestion that the photocells might point away from the light, with their wires departing on the side nearest the light. Yet this is exactly what happens in all vertebrate retinas. Each photocell is, in effect, wired in backwards, with its wire sticking out on the side nearest the light. The wire has to travel over the surface of the retina, to a point where it dives through a hole in the retina (the so-called “blind spot”) to join the optic nerve.

Another evolutionary biologist George Williams further argued,

There would be no blind spot if the vertebrate eye were really intelligently designed. In fact, it is stupidly designed.

Douglas Futuyma published a textbook on evolution arguing that

no intelligent engineer would be expected to design [the] functionally nonsensical arrangement of cells in the human retina.

Molecular biologist Nathan Lents wrote in 2015,

The photoreceptor cells of the retina appear to be placed backward, with the wiring facing the light and the photoreceptor facing inward…. This is not an optimal design for obvious reasons. The photons of light must travel around the bulk of the photoreceptor cell in order to hit the receiver tucked in the back. It’s as if you were speaking into the wrong end of a microphone.

These evolutionists argued that unguided evolution would more likely be an explanation than an intelligent designer.

Retina Found to Show No Bad Design Features

External Eye

Further science and research have shown the arrangement of neural lays in the human retina to be supportive of design – not against it. These surprising findings show the arrangement of neurons supports visual function in a way that was not foreseen by all the evolutionary biologists listed above.

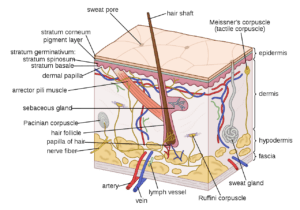

The light-sensing cells in the retina are the most metabolically active cells in the human body. (Futterman). About seventy-five percent of the blood flow to the eye flows through capillaries called the “choriocapillaris.” This dense network of capillaries is located just behind the light-sensitive area. It is from this dense network of capillaries that nutrients and oxygen first travel to cells called the “retinal pigment epithelium” (RPE).

The RPE transports oxygen and nutrients to the light-sensitive cells but they also have other essential functions. They absorb scattered light thereby improving the optical quality of the eye. They also remove toxic chemicals that are produced in the visual process.

Richard Young showed that the light-sensitive cells continually renew themselves by shedding discs at the end closest to the RPE while replacing them with new discs at the other end. The RPE engulfs the shed discs and neutralizes the toxins produced by the visual process.

The RPE stores Vitamin A which is important in the regeneration of photopigments. These pigments are all bleached when exposed to light and consist of rhodopsin (found in the rods for night vision), and one pigment for each of the three primary colors. The RPE also synthesizes the structural material between and separating the photoreceptor cells (glycosaminoglycans). Finally, the blood flow coursing through the pigment epithelium turns out to be even greater than that required to nourish the photoreceptor cells. This extra blood flow serves as a heat sink to keep the neural layer from overheating and damaging itself in the visual process.

The RPE has several mechanisms for dealing with the toxins that are produced by the visual process. These toxins are highly chemically reactive and would damage the sensitive tissues in the back of the eye. These mechanisms include various enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidases which break down oxidizing molecules such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide. Other antioxidants include Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol) and ascorbic acid (vitamin C).

The RPE also contains pigment granules of melanin – the same material found in human skin giving it color. These melanin granules absorb scattered and excess light in order to improve visual acuity allowing people to see better. Between 25% and 33% of all light entering the eye is absorbed by these granules. It turns out that the spectral absorption of melanin increases with decreasing wavelength and it is the shorter wavelengths that carry the greatest energy and produce more damage. This arrangement helps prevent damage to the sensitive neural cells by reducing their exposure to shorter more energetic wavelengths.

But what about vision? The central claim of evolutionists has been the arrangement of the visual cell behind other neurons is backward to the “better” arrangement of primitive cephalopods (such as the squid eye).

Recent science shows that the situation is not as simple as would first appear (pun intended). A team of German investigators revealed the presence of “radial glial cells” that are associated with the retina that act as optical or visual fibers. These “Muller cells” are fibers in the direction of light propagation through the retina which allows them to transmit light from the surface of the retina to the photoreceptors. These remarkable cells serve as a low-scattering transmitter of light from the retinal surface with little distortion. These cells compensate for the “bad design” of the retina while preserving the sensitive sight region of the retina from damage due to direct light exposure.

Sweating about Sweat

By Tomáš Kebert & umimeto.org – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

As noted in the introduction to this article, one evolutionary biologist, Matan Shelomi, is concerned about sweat and more specifically about the cooling mechanisms of various animals. He notes,

Life most mammals, we sweat to maintain our temperature, but most animals do not have as many sweat glands as we do. We are the least efficient thermoregulators in the mammal world; only apes and (oddly) horses have as many sweat glands, mostly in the armpits, as we do.

The assumptions surrounding his objections to design have little relevance, however. It would seem as though the evolutionary biologist has little knowledge concerning the broader facts of biology other than his evolutionary specialty.

We are all very familiar with dogs and take for granted the urban knowledge that dogs do not sweat. But in actuality, they do.

Most dogs are covered with a thick coat of fur in order to provide insulation and protect their body temperature. Sweating from a fur-covered body would provide little efficacy to cool the animal down because the sweat would be absorbed by the animal’s fur and not dissipate heat effectively.

Dogs do have sweat glands on the pads of their feet and on the nose. A dog produces a trail of sweaty footprints walking across a dry surface proving the ability of fur-covered animals to sweat and help cool themselves.

Dogs also rely on other mechanisms to help reduce their body temperature on a hot day. The primary cooling mechanism is to pant. Breathing quickly over the wet surfaces of the mouth and lungs helps dissipate heat through evaporative cooling much in the same way as a sweaty human body does. The Textbook of Small Animal Surgery by Douglas H. Slatter notes,

Merocrine glands are coiled, simple, tubular glands found mainly in the footpads of dogs; they empty directly onto the epidermal surface. Sweat glands are better-developed n the canine breeds that have long, fine hair. Sweat glands in the hair skin of dogs, and cats (apocrine glands) do not participate actively in the central thermoregulatory mechanisms but protect the skin from the excessive rise in temperature.

The idea that somehow sweating in a dog needs to be similar in a very different animal such as a man seems to be simplistic at best and hopefully not representative of the author’s general biology fund of knowledge.

Summary About Bad Design Features

The panda’s thumb is an unusual contrivance requiring the manipulation of several bones in the wrist of the panda. It is not similar to the opposable thumb of humans but seems to be well adapted to its purpose.

Bamboo shoots comprise more than 99% of the giant panda’s diet and so any functionality compromise of its grasping paw could seriously adversely affect its survival.

While its non-opposable thumb-like structure may seem a design deficiency, further evaluation with CAT and MRI scans reveal its utility. In fact, these investigators marvel at its being of “extraordinary” utility in its ability to perform its function over prolonged periods of time. This should lay to rest the canard that the panda’s thumb is an argument against intelligent design.

References

Sidney Futterman, “Metabolism and photochemistry in the retina,” pp. 406-419 in Adler’s Physiology of the Eye, ed. Robert A. Moses, 6th ed. (St. Louis: C. V. Mosby, 1975), 406

Bad Design Features

Bad Design Features