Albert Camus

Albert Camus and Religious Belief

By Photograph by United Press International – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs Division; under the digital IDcph.3c08028; This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons: Licensing for more information., Public Domain, Link

Albert Camus was a French philosopher who was prominent during the 1950s. He won the Nobel Price in Literature at the age of 44 in 1957 as one of the youngest ever to achieve this milestone. Many of these works were required reading in college philosophy courses, including The Stranger, The Plague, The Myth of Sisyphus, The Fall, and The Rebel.

The French newspaper Le Monde considered The Stranger as one of the 100 Books of the Century, ranking number one. There is a reason why this prestigious paper listed a work from Camus as the most important of the last century. It gave the French atheist intellectuals a framework enabling them to deal with the meaninglessness of life.

He was born in French Algeria into poverty and would later study philosophy at the University of Algiers. He was very poor during his childhood as his father died during World War 1. He caught a teacher’s attention (Louis Germain) and obtained a scholarship at a prestigious secondary school near Algiers.

Camus developed tuberculosis and moved out of his home to not transmit the disease to his family. He stayed with his uncle Gustave Acault, a butcher, who influenced the young Camus toward philosophy. He was impressed with the ancient Greek philosophers and with Friedrich Nietzsche.

He enrolled at the University of Algiers in 1933 and achieved his degree in philosophy in 1936. He came to believe in atheism after studying the works of Nietzsche and Schopenhauer

He had the unfortunate circumstance to be in France during the German occupation and joined the French Resistance serving as editor-in-chief of Combat – an outlawed newspaper.

He was a celebrity figure after the War and gave many lectures around the world, especially on college campuses where popular ideas of labor unionism and anarchism were popular. His major philosophical idea was that of absurdism.

Absurdism of Albert Camus

Camus’ philosophy tried to a meaning for life in an absurd world in which all of our accomplishments will likely be forgotten only a few years after death. Camus recognized the injustice of life all must recognize: good people often are faced with terrible hardships while evil people often thrive. Christianity resolves this dilemma by noting that both good and evil people receive ultimate justice in the afterlife. But how to resolve this issue without believing in religion?

Camus’ philosophy concerned the ultimate meaning of life – whether indeed there was any ultimate meaning. He proposed that life is utterly meaningless and random in that universe that is irrational and indifferent to our suffering. Camus proposed that life has no inherent meaning. We come into this life by accident and that life is ultimately meaningless and therefore “absurd.”

Existential philosophers have suggested that such a conclusion regarding the absurdity of life might lead to despair. This despair might logically lead to suicide if the suffering became too great. What is the point of living a meaningless life only to suffer endless, progressive despair?

But Camus stated that a meaningless universe might actually allow us to more fully experience life. A religious person, for example, might limit their life choices recognizing their ultimate judgment in the afterlife, while the person without such belief would indulge themselves in the pleasures of the world because there is no judgment to fear.

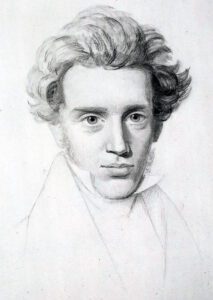

Soren Kierkegaard and the Futility of Life

Soren Kierkegaard – By La Biblioteca Real de Dinamarca – https://www.flickr.com/photos/45270502@N06/9645352916/, Public Domain, Link Kierkegaard

Kierkegaard is considered to be the first existentialist philosopher. He tried to find an ultimate meaning for life that somebody could live and die for – that would have the ultimate meaning and provide a reason for the suffering we find on earth.

Kierkegaard also concluded that much of our existence cannot be rationally explained. Why do evil people thrive while good people suffer? Because there is no rational explanation we need to find something outside of ourselves that can give meaning to life. He proposed religion as the answer, and that people should take a leap of faith and find a higher purpose that would give ultimate meaning to life. He proposed this solution even though there is no solid proof that there is any validity to religion, and that there is any place known as heaven.

Albert Camus called this faith solution “philosophical suicide.” He believed religion to be a “sell-out” along with any other meaning we might give to life. Any such meaning is nothing more than constructs of the human mind that have no demonstrable basis.

Camus argued there is no proof that the universe has any transcendent meaning, and if it does, we do not have that evidence. He noted in his philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus,

I don’t know whether this world has a meaning that transcends it. But I know that I do not know that meaning and that it is impossible for me just now to know it. What can a meaning outside my condition mean to me? I can understand only in human terms.

Albert Camus’ Resolution of the Meaningless of Life

Camus felt that the universe was indifferent to how we live our lives and that there are no universal values, no “objective morality.” To Camus, there is no divine plan for existence, and everything that happens to mankind happens randomly.

Camus believed that we are rational beings and that we struggle with our predicament in finding any meaning in life because we live in an irrational and indifferent universe. Camus believed finding any ultimate meaning in the universe is absurd because there is none. If we think we have found such a meaning, it will slide through our hands like water on closer observation.

The usual pathway through life most take is to grit our collective teeth and bear it. The culturally acceptable pathway whereby we live life by going to work five or six days a week and spending our recreational time in frivolous ways might lead to despair. This despair might then prod us to wonder what the point of all this activity and suffering is.

Many existentialist philosophers end the story there and argue there is no point to all this despair and suffering, and that a logical action might be to end it all with suicide.

As Camus noted,

Rising, streetcar, four hours in the office or the factory, meal, streetcar, four hours of work, meal, sleep, and Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday and Saturday according to the same rhythm. This path is easily followed most of the time. But one day the “whjy” arises and everything begins in that weariness tinged with amazement.

The absurdity is trying to find any rationality in an indifferent world – there is none.

Religion and Existentialism

Camus noted that there are two ways we can live according to this absurdity: we can live it, or we escape from it.” Camus believed most people will just “live it.” Camus believed that many clever people have created answers to satisfy philosophical and existential questions, often in the form of religion.

Other forms of control in addition to religion are secular substitutes, including nationalism or belonging to fraternal societies which do good (or harm) to society. This is proposed as the reason why the increasingly secular society in Germany after World War 1 readily accepted itself as a “master race” that should control the world.

Camus believed the problem with these “solutions” is that they require us to put aside our rational minds and choose to believe in things without any proof. This belief might include concepts counter to our common experiences, such as belief in miracles or an afterlife.

A more direct approach to escape the absurd – the attribution of purpose where there is none – is suicide. The problem with this “solution” is that it is a form of surrender to the problem. It admits that the hopelessness and despair from an ultimately meaningless solution are unbearable.

Albert Camus’ Solution to a Meaningless Life

The philosophically sound solution to this problem of living a meaningless life is to question whether living such a life is necessarily wrong. According to Albert Camus, it is not.

Camus argues that it is possible to achieve pleasure and satisfaction even when living an ultimately meaningless life. Camus argues that accepting life in a world without meaning is to forego any illusions of meaning. It is more intellectually honest to base life’s choices on what makes us happy than what might provide meaning as, ultimately, life has more meaning.

Since there is no afterlife or judgment, we can completely focus on this life to extract from it every sliver of happiness that might be available.

Even more importantly, when there are no transcendent morals or values – no “objective morality” – we can concentrate on creating our own set of morals and values.

Rebellion

Rebellion against the meaningless of life.

Camus believed our only control in this meaningless world is our thoughts and actions. We can choose to rebel against the culturally normative behavior which brings us no happiness in a meaningless world. Instead, we can choose to live on our own terms- to be like Frank Sinatra and “live it my way!”

Living a life of despair in a meaningless world means rejecting any hope of finding any purpose. It means living in indifference to the future which may never come, and in fact, living for ourselves only and not for others. There is no altruistic behavior in Camus’ world of dealing with the absurd, as that behavior would necessarily deprive us of some smidgeon of pleasure we might otherwise have.

Camus sees this life as noble, accepting life’s ultimate absurdity and living for his pleasure. He notes,

Hence what he demands of himself is to live solely with what he knows, to accommodate himself to what is, and to bring in bothering that is not certain. He is told that nothing is. But this at least is a certainty. And it is with this that he is concerned: he wants to find out if it’s possible to live without appeal.

Living without appeal means living for the present moment and not wanting anything from a conceptual future that might never come.

To imagine what it is like to live a despairing life without appeal, Camus pointed to the Greek legend of Sisyphus. This person had the unfortunate circumstance of offending the Greek gods and was sentenced to roll a stone up a mountain only to let it fall back down the mountain for all eternity. This is truly a meaningless life that should be associated with ultimate despair.

However, Camus opined it might still be possible to achieve meaning and happiness in the existence of Sisyphus. Meaning for Sisyphus is achieved in the act itself, which Camus believed should be sufficient to be content in a hopeless life. This might be somewhat akin to Martin Luther’s proposal that every vocation – even the most menial – has some purpose and satisfies God.

The Greek gods condemned Sisyphus on the idea that nothing is more meaningless and dreadful than pushing a rock up a mountain only to let it fall back down when it reaches the top. Camus would say that this attribution of meaninglessness depends on our position toward that task. What is it possible to find joy in despair, and what if in this joy, we refuse to accept the misery that life throws at us?

The happiness or despair we might feel with any external act involving us is determined by our reaction to that external act. We ultimately make the final decision as to whether that act makes us happy or not.

There is nothing more rebellious than in finding joy in what should result in misery.

But is that all there is to life – to be a rebel?

Albert Camus Meets Christianity

Howard Mumma was a Methodist preacher from the United States who would spend the summer preaching at an English-speaking church in Paris. One Sunday, he recognized Albert Camus – of all people – sitting in the pews in his church. Camus seemed to be searching for more than just being a “rebel” against the meaninglessness of life.

Mumma wrote in his book Albert Camus and the Minister,

Mumma: You have said to me again and again that you’re dissatisfied with the whole philosophy of existentialism and that you are privately seeking something that you do not have.

Camus: Yes, you are exactly right, Howard. The reason I have been coming to church is that I am seeking. I’m almost on a pilgrimage – seeking something to fill the void that I am experiencing – and no one else knows. Certainly, the public and the readers of my novels, while they see that void, are not finding the answers in what they are reading. But deep d0own, you are right – I am searching for something that the world is not giving me.

Mumma: Albert, I congratulate you on this. I think that I want to encourage you to keep searching for meaning and something that will fill the void and transform your life. Then you will arrive in living waters where you will find meaning and purpose.

Camus. Well, Howard, you have to agree that in a sense we are all products of a mundane world, a world without spirit. The world in which we live and the lives which we live are decidedly empty.

Mumma: It does often seem that way, I concede.

Camus: Since I have been coming to church, I have been thinking a great deal about the idea of a transcendent, something that is other than this world. It is something that you do not hear much about today but I am finding it. I am hearing it here, in Paris, within the walls of the American Church. After all, one of the basic teachings that I learned from Sartre is that man is alone. We are solitary centers of the universe. Perhaps we ourselves are the only ones who have ever asked the great questions of life. Perhaps, since Nazism, we are also the ones who have loved and lost and who are, therefore, fearful of life. That is what led us to existentialism. And since I have been reading the Bible, I sense that there is something – I don’t know if it is personal or if it is a great idea or powerful influence – but there is something that can bring meaning to my life. I certainly don’t have it but it is there. On Sunday mornings, I hear that the answer is God.

Eventually, Mumma records Camus saying,

Howard, I am ready. I want this. This is what I want to commit my life to.

The great atheist existentialist Camus committed his life to Christ.

This conversation occurred in the summer of 1959, just before Mumma returned to the United States. Four months later, on January 4, 1060, Camus died in a car crash. Most of his huge foll0wing never knew that he turned from the meaninglessness of atheism to the life of purpose in Christ.

Summary

Finding meaning in life is one of the reasons we are here; we need to discover life has meaning. In the atheist philosophy there is no ultimate meaning for life – it is, as Camus might have said, “absurd.”

Most atheists would readily acknowledge this conclusion recognizing that in one hundred years, it is likely their entire life will have been forgotten even by their family. Their accomplishments, dreams, aspirations, hopes, and fears will all be forgotten. It will have been as though they had never lived.

Some atheists assert this makes their life more meaningful – not less – because “you only live once” and so you have to get everything out of life you can. They often also assert their philosophy is somehow more “noble” for recognizing the meaninglessness of life as opposed to Christians who believe in a heaven that can never be seen or proven.

But it also can not be proven there is no heaven, and there is mounting evidence everywhere that there is a transcendent being who orders the universe and has brought everything that is into being.

It is ultimately a choice – the choice Nietzsche made which led him into despair, or the one that Camus made that gave meaning to his life. Both were avowed atheists but ultimately came to opposite conclusions.