Being an Agnostic

An agnostic is somebody who states he “does not know” about the existence of God. Being an agnostic means you accept the possibility that there might be a God but remain unconvinced of his existence.

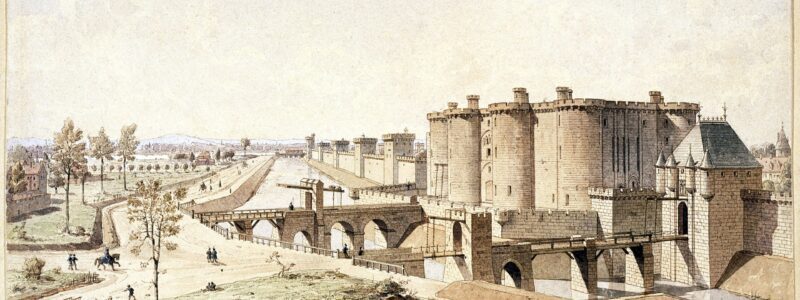

Thomas Huxley – By Lock & Whitfield – original w:Woodburytype, Public Domain, Link

The term was originally proposed by Thomas Huxley in 1869 who said,

It simply means that a man shall not say he knows or believes that which he has no scientific grounds for professing to know or believe.

The basic idea of Huxley’s objection is that the existence of God is unknowable – it is not possible to say without a doubt whether God either exists – or not. Huxley presented his philosophy of agnosticism at a meeting of the Metaphysical Society in 1869.

Huxley defined his agnostic position as follows,

I have never had the least sympathy with the a priori reasons against orthodoxy, and I have by nature and disposition the greatest possible antipathy to all the atheistic and infidel school. Nevertheless I know that I am, in spite of myself, exactly what the Christian would call, and, so far as I can see, is justified in calling, atheist and infidel. I cannot see one shadow or tittle of evidence that the great unknown underlying the phenomenon of the universe stands to us in the relation of a Father [who] loves us and cares for us as Christianity asserts. So with regard to the other great Christian dogmas, immortality of soul and future state of rewards and punishments, what possible objection can I—who am compelled perforce to believe in the immortality of what we call Matter and Force, and in a very unmistakable present state of rewards and punishments for our deeds—have to these doctrines? Give me a scintilla of evidence, and I am ready to jump at them.

According to the philosopher William Rowe , agnosticism is the view that reason is unable to post sufficient rational grounds for the belief that God exists or not.

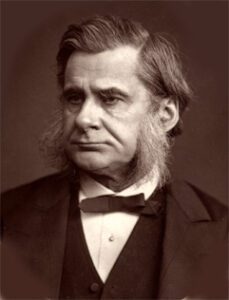

Bertrand Russell – By Anefo – http://proxy.handle.net/10648/a96fca82-d0b4-102d-bcf8-003048976d84, CC0, Link

The twentieth-century philosopher Bertrand Russell contended that it is not possible to absolutely prove the existence of a God, and therefore he could not believe in the existence of one, He noted,

An agnostic thinks it impossible to know the truth in matters such as God and the future life with which Christianity and other religions are concerned. Or, if not impossible, at least impossible at the present time.

Are Agnostics Atheists?

No. An atheist, like a Christian, holds that we can know whether or not there is a God. The Christian holds that we can know there is a God; the atheist, that we can know there is not. The Agnostic suspends judgment, saying that there are not sufficient grounds either for affirmation or for denial.

The proof of God’s existence would have to be very dramatic such as a voice from the sky,

I think that if I heard a voice from the sky predicting all that was going to happen to me during the next twenty-four hours, including events that would have seemed highly improbable, and if all these events then produced to happen, I might perhaps be convinced at least of the existence of some superhuman intelligence.

Robert Ingersoll – By Mathew Brady – Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cwpbh.05180. CALL NUMBER: LC-BH832- 31186 <P&P>[P&P], Public Domain, Link

Is there a supernatural power—an arbitrary mind—an enthroned God—a supreme will that sways the tides and currents of the world—to which all causes bow? I do not deny. I do not know—but I do not believe. I believe that the natural is supreme—that from the infinite chain no link can be lost or broken—that there is no supernatural power that can answer prayer—no power that worship can persuade or change—no power that cares for man.

He then went on to say,

Is there a God? I do not know. Is man immortal? I do not know. One thing I do know, and that is, that neither hope, nor fear, belief, nor denial, can change the fact. It is as it is, and it will be as it must be.

Bernard Bell on Agnosticism

Bernard Bell was an American Christian author, educator, Episcopal priest, and conservative commentator. He was particularly interested in the interplay between science and religion pertaining to the elucidation of Truth. He received praise from many intellectuals of the day such as Albert Jay Nock, T. S. Eliot, Richard M. Weaver, and Russell Kirk, and was featured on the cover of Time magazine. While his name might not be familiar to many today, he was an intellectual giant of his time.

Bell was experienced presenting the Christian worldview to agnostic students as he was responsible for running a college affiliated with the Episcopal Church. Even though it was a “church school”, many of its students doubted the religious upbringing of their youth, or never really accepted the Christian worldview. at all.

Bell believed going through a period of agnosticism was not an uncommon and perhaps even natural part of the development of faith in young adults as they leave their parent’s influence and try to establish their own faith and identity.

Bell tried to show students the positive aspects of the Christian life, and how religion and science were sister disciplines and not divorced from each other. They each had their own means for determining the truth, one in the physical realm while the other in the spiritual one.

He cited the long list of scientists who were predominantly religious noting that there was no real antagonism between religion and science, believing that any conflict is promulgated by “demi-educated” scientists and theologians. He noted that during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, the natural relationship between science and religion was severed leading to scientific materialism and religious fundamentalism.

He felt that materialistic science denies any non-measurable realities the inner life of humans such as love, beauty, goodness, creativity, and expressed these to behavioral theory and biochemical reactions. Religious fundamentalism, on the other hand, promulgated a narrow interpretation of Scripture and demanded an anti-scientific mindset to supports its beliefs.

He eventually wrote a thesis explaining the philosophical reasons as to how he became at first theist, and then a Christian,

Scientific data, observed by human senses and processed by human reason, is insufficient for discovering Truth. Modern peoples’ underlying anxiety is the result of dependence upon such incomplete data for innovating technology and infrastructure. Our ability to reason is not a way to discover Truth but rather a way to organize our knowledge and experiences somewhat sensibly. Without a full, human perception of the world, one’s reason tends to lead them in the wrong direction.

Beyond what can be measured with scientific tools, there are two other types of perception: one’s ability to communicate inner truths through creative expression and one’s ability to “read” another person and find harmony with them, which we call love. One’s loves cannot be dissected and logged in a scientific journal, but we know them far better than we know the surface of the sun. They show us an undefinable reality that is nevertheless intimate and personal, and they reveal qualities lovelier and truer than sensory facts can provide.

Reality, as experienced by humans, must be understood through all three ways of knowing: science, creative expression, and love. Only by experiencing this Reality as a person can we come closer to the Truth, for an ultimate Person can be loved, but a cosmic force cannot. A scientist can discover peripheral, material truths, but a lover is able to get at the Truth.

There are many reasons to believe in God, but they are not sufficient to convince an agnostic. It is not enough to believe in an ancient holy book, even though when it is accurately analyzed without bias, it proves to be more trustworthy and admirable than what one is taught in school. Neither is it enough to realize how probable it is that a personal God would have to show human beings how to live, considering they have so much trouble on their own. Nor is it enough to believe for the reason that, throughout history, millions of people have known Reality only through religious experience. The aforementioned reasons may warm one toward religion, but they fall short. However, if one presupposes that God is, in fact, a knowable, loving person, as an experiment, and then lives according that religion, he or she will suddenly come face to face with experiences previously unknown. One’s life becomes full, meaningful, and fearless in the face of death. It does not defy reason but exceeds it.

Because God has been experienced through love, the orders of prayer, fellowship, and devotion now matter. They create order within one’s life, continually renewing the “missing piece” that had previously felt lost. They empower one to be compassionate and humble, not small-minded or arrogant.

No truth should be denied outright, but all should be questioned on the scale of evidence. Science reveals an ever-growing vision of our universe that should not be discounted due to bias toward older understandings. Reason is to be trusted and cultivated. To believe in God is not to forego reason or to deny scientific facts, but to venture into the unknown and discover for oneself what is True.

Etymology

The derivation of the word “agnostic” is from the Greek meaning without “gnosis” or knowledge. The term as it is used today reflects its etymology in that believes in God cannot be known.

Types of Agnosticism

Adherents to agnosticism can be along three lines in inquiry,

Some don’t care, have not investigated the subject of God and their eternal destiny, and are only interested in the present without any consideration of the future.

- “Hard” agnosticism states they not only do not know whether there might be a God but also insist that it is not possible to determine with certitude ever that God exists

- “Soft” agnosticism proposes they do not know whether there might be a God but hold open the possibility that sometime in the future it might be possible to make that determination.

Most agnostics are the “soft” variety, refusing to make a decision either for or against God unless there is further evidence on either side.

The soft agnostic has taken the position that he will not accept the Christian worldview because there is insufficient evidence attesting to its truth. The agnostic does not state there is no God; simply that there is not sufficient evidence for that belief.

Usually the agnostic places little value on belief comfortable in their own lifestyle and is not actively engaged in seeking evidence toward to against belief and has not delineated the type or extent of evidence which would be required for them to make a positive decision toward God.

The Argument for Faith from Pascal’s Wager

Pascal – By unknown; a copy of the painting of François II Quesnel, which was made for Gérard Edelinck en 1691[réf. nécessaire]. – Own work, CC BY 3.0, Link

Pascal set forth his challenge in the form of a wager. The wager takes the position that there is evidence for theism but it is not absolutely convincing to agnostics. Without going into what might represent such convincing evidence, Pascal challenges agnostics to re-consider their position in terms of winnings with respect to a wager concerning the probability of there being – or not being – a God.

An explanation of Pascal’s wager was put forth in the book, Fundamentals of the Faith by Peter Kreeft,

Most philosophers think Pascal’s Wager is the weakest of all arguments for believing in the existence of God. Pascal thought it was the strongest. After finishing the argument in his Pensées, he wrote, “This is conclusive, and if men are capable of any truth, this is it.” That is the only time Pascal ever wrote a sentence like that, for he was one of the most skeptical philosophers whoever wrote.

Suppose someone terribly precious to you lay dying, and the doctor offered to try a new “miracle drug” that he could not guarantee but that seemed to have a 50-50 chance of saving your beloved friend’s life. Would it be reasonable to try it, even if it cost a little money? And suppose it were free—wouldn’t it be utterly reasonable to try it and unreasonable not to?

Suppose you hear reports that your house is on fire and your children are inside. You do not know whether the reports are true or false. What is the reasonable thing to do—to ignore them or to take the time to run home or at least phone home just in case the reports are true?

Suppose a winning sweepstakes ticket is worth a million dollars, and there are only two tickets left. You know that one of them is the winning ticket, while the other is worth nothing, and you are allowed to buy only one of the two tickets, at random. Would it be a good investment to spend a dollar on the good chance of winning a million?

No reasonable person can be or ever is in doubt in such cases. But deciding whether to believe in God is a case like these, argues Pascal. It is, therefore, the height of folly not to “bet” on God, even if you have no certainty, no proof, no guarantee that your bet will win.

Atheism is a terrible bet. It gives you no chance of winning the prize.

To understand Pascal’s Wager you have to understand the background of the argument. Pascal lived in a time of great skepticism. Medieval philosophy was dead, and medieval theology was being ignored or sneered at by the new intellectuals of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century. Montaigne, the great skeptical essayist, was the most popular writer of the day. The classic arguments for the existence of God were no longer popularly believed. What could the Christian apologist say to the skeptical mind of this age? Suppose such a typical mind lacked both the gift of faith and the confidence in reason to prove God’s existence; could there be a third ladder out of the pit of unbelief into the light of belief?

Pascal’s Wager claims to be that third ladder. Pascal well knew that it was a low ladder. If you believe in God only as a bet, that is certainly not a deep, mature, or adequate faith. But it is something, it is a start, it is enough to dam the tide of atheism. The Wager appeals not to a high ideal, like faith, hope, love, or proof, but to a low one: the instinct for self-preservation, the desire to be happy and not unhappy. But on that low natural level, it has tremendous force. Thus Pascal prefaces his argument with the words, “Let us now speak according to our natural lights.”

Imagine you are playing a game for two prizes. You wager blue chips to win blue prizes and red chips to win red prizes. The blue chips are your mind, your reason, and the blue prize is the truth about God’s existence. The red chips are your will, your desires, and the red prize is heavenly happiness. Everyone wants both prizes, truth and happiness. Now suppose there is no way of calculating how to play the blue chips. Suppose your reason cannot win you the truth. In that case, you can still calculate how to play the red chips. Believe in God not because your reason can prove with certainty that it is true that God exists but because your will seeks happiness, and God is your only chance of attaining happiness eternally.

Pascal says, “Either God is, or he is not. But to which view shall we be inclined? Reason cannot decide this question. [Remember that Pascal’s Wager is an argument for skeptics.] Infinite chaos separates us. At the far end of this infinite distance [death], a coin is being spun that will come down heads [God] or tails [no God]. How will you wager?” (From Fundamental of the Faith by Ignatius Press

Summary

Agnosticism is often thought by its supporters to be the most defensible position concerning the existence of God. There is simply not sufficient evidence one way or the other for this individual and therefore they refuse to make a determination.

But time marches on.

Eventually, no decision becomes a negative decision; there is, in reality, no middle ground because in life you either serve God or you do not; it is a binary choice. An agnostic position is not to serve God.

The decision not to follow God does not mean you cannot be a “good person” – to give to charity, to be good to your neighbors and to be righteous in outward appearance. But if you take Pascal’s wager and bet against God, there might just be eternal consequences.